By Sandip Roy

Hansal Mehta’s Aligarh, by dint of timing, is already an “important” movie. LGBT rights and Section 377 are back in national news thanks to a curative petition up for consideration by the Supreme Court. Vigilantes beating up someone whose values they do not like, intolerance of the “other”, are all distressingly current.

A lament in the film about a time when ideological differences in universities were resolved by debate rather than “khoon kharaba” sounds almost prescient. But contemporary relevance can be a double-edged sword. The greatest disservice to Aligarh would be to view it as a pamphlet for LGBT rights.

It is really a story about loneliness, aging and vulnerability. Manoj Bajpayee as SR Siras, professor of Marathi at Aligarh University, is scrunched from his very first appearance, sitting on a rickshaw on a rusty foggy night. He is a reclusive man who tries to take up as little space as possible, only relaxing when he is in his room, listening to his beloved Lata Mangeshkar, swirling a glass of whisky.

Yet even his room is no sanctuary. It is here that his life unravels as camera-wielding goons burst in and film him in bed with a young rickshawpuller. His university colleagues rush in right behind them and soon Siras is chargesheeted, dismissed and evicted.

Fortunately for him, this occurs in that brief period between the Delhi High Court decriminalizing consensual homosexual acts in 2009 and the Supreme Court recriminalising them in 2013. That short-lived “Delhi Spring” allows for a strong case against his dismissal, but only if Siras comes out as gay, something that’s excruciatingly public for a man who balks at even the word “gay”.

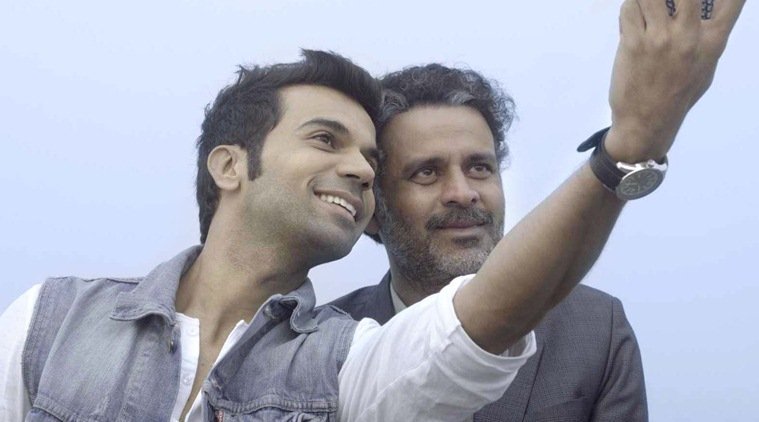

Bajpayee’s Siras could easily have keeled over self-righteously into a tragic figure, weighed down by his humiliations. But sometimes his face crinkles into a smile and you get a glimpse of another man. When Deepu Sebastian, the eager young rookie reporter played by an ebullient Rajkumar Rao, suddenly asks him for a selfie on a boat on the Ganga, Bajpayee’s face lights up. I look terrible, he protests.

“Sir, you are goodlooking,” says Sebastian. “Thank you,” replies Siras almost bashfully. It’s a tender moment of the vulnerability of an older person who has not heard that compliment in a long time, and still thirsts for it even if he cannot say it.

The almost tentative chemistry between Sebastian and Siras give the film its emotional core even though much is left unexplored there. Why was Sebastian, a young reporter on probation, so taken with that story? Did he eye it as a big break and then somehow get caught up more than he anticipated?

Some scenes are sharply etched. For example, Sebastian asking Siras those awkward questions that are unavoidable in reporting –Were you suspended because you are gay? Some scenes are more questionable. A sexual encounter on the office terrace between Sebastian and a woman, who happens to be his editor and boss, intercut with scenes of Siras and his lover in bed, is presumably meant to convey a message about the universality of desire and consenting adults. It however raises more troubling questions than it answers. An editor propositioning her subordinate, that too a subordinate on probation, blurs the meaning of consent in rather disturbing ways.

Unlike Neerja, the other “based on real life” film in theatres now, Aligarh is not a story about an ordinary person who is tested by fire and emerges extraordinary. Siras remains till the end a diffident man, an accidental activist, almost as uneasy with the outsized clamour of a rainbow pride parade as he is with his prying homophobic colleagues.

It is to Hansal Mehta and writer-editor Apurva Asrani’s credit that they resist the urge to mold him into a more recognizable filmi hero that we can root for. That restraint gives Aligarh its most memorable tender moments. As Siras says poetry is not in the words, it’s hidden behind the words, in silences, in pauses. The film lives up to that. Put another way, in terms of Siras’ beloved Lata, it is much more a wistful Aap Ki Nazron Ne Samjha than it is a defiant Pyar Kiya to Darna Kiya.

Watching Aligarh in the middle of a weekday afternoon meant there were only a handful of people in the theatre. A few were couples and as the darkness settled around us it was clear that for some of them, their interest in the film was minimal. It was dark. The theatre was largely empty. It was an ideal setting for a bit of stolen romance. As the couple behind me giggled, and chatted, and murmured endearments, oblivious to the drama unfolding on screen, I was annoyed. But then I realized this was a film that had, at its heart, our rather fragile right to privacy. Perhaps it was not so inappropriate that Aligarh could afford a young couple a few hours of that precious commodity in a bustling nosy city.

Siras, I feel, would not have minded.