I lived away from India for many years. When I returned to Kolkata from California, I knew I would need a cultural guide to reintroduce me to my city again. Luckily, my mother watched Bengali soaps. She coordinated her appointments with the doctor around her soap schedule. Actually, the elderly retired neighbourhood doctor coordinated his chamber hours with his favourite soap as well. “I will leave promptly at 7:20”, he warned us when we called for an appointment. “My serial starts at 7:30.”

The markers of my city had changed. Our old two-storey house with its terrace where the bougainvillea grew wild was gone, replaced by a characterless apartment building. The old single-screen movie theatres were shuttered. Swanky multiplexes had come in their place. Street names had changed, even bus routes. New restaurants were the rage, instead of the old classics.

But in the soaps I finally found the reassurance of my lost city.

This was a world where the only sign of modernity was the cellphone. Otherwise, little had changed. Mothers-in-law still called their daughters-in-law “Bouma” or “Daughter-in-law”. Or Boro-bouma, mejo-bouma, chhoto-bouma. (Older daughter-in-law, middle daughter-in-law, younger daughter-in-law). There were always at least three. The men worked and did other such manly things like drink tea the women made. When they were not making tea for the menfolk, the women sat around the house impeccably dressed in starched saris and schemed against each other. That was obviously pure fiction. In the real middle-class Kolkata, they would be scheming in their nighties.

But the serials harkened back to another Kolkata where saris were perfectly pleated and maids never talked back. My own cousins had scattered to the winds, but here the joint family (+ wicked Mejo-bouma’s even more wicked mother + widowed cousin sister + not-related-but-almost-like-family-son-from-the-ancestral village) all lived together and had breakfast together every morning. Here the grandchildren still crowded around their old grandmother on her giant bed instead of playing on their iPads and cellphones. Sometimes, the doorbell or the landline would ring, and everyone would stare at each other, and discuss excitedly who it might be – but no one would move to answer it. At least not until after the ad break.

Admittedly these were not the brightest people even though they always ran mysterious off-screen business empires. I could tell at a glance which daughter-in-law was the most scheming (the more the makeup, the more the scheming), but the rest of the family remained blissfully unaware. They were also prone to getting into accidents and losing their memory. And if they had twins, one was guaranteed to be conniving. It was clearly an occupational hazard for a serial character.

Misogyny was their bread and butter even if their target audience was women. In one serial, the only positive female characters were the young protagonist’s mother and she was long dead and the old grandmother who mostly wrung her hands helplessly. The good daughter-in-law would routinely get expelled from the house, her honour wrongly besmirched, much like Sita. Unlike Sita she would come back in disguise. A fool-proof disguise in Bengali middle-class households was to dress as the “Hindustani maid”. It required no makeup, just an iffy accent, a shrieking voice and a sari draped around her head. No one would recognise her, not even her own husband. Until she made tea. Then and only then would he suspect this maid might be no ordinary maid.

Sometimes I was confused by the revolving door between serials. The coquettish daughter-in-law from 6:30 pm could show up as the demure draped bahu at 7:00 pm. The patriarch from 6:00 pm would suddenly disappear for days to be the industrialist at 7:30 pm until he went into a convenient coma there and could return fulltime to his 6:00 pm role. When my mother went to the doctor and instructed me to watch her serials, their plots would merge into each other like melting plastic.

Often I was frustrated. “But nothing happens”, I would tell her in exasperation. Then one day, I realised that was the point. In Kolkata, nothing much happens and in the serials nothing much happens as well. Just with more jewellery and more saris.

My mother is part of a generation where too much has happened around them. The children have moved to Boston and Bengaluru. The grandchildren are growing up in faraway places, their Bengali accented and broken. Smartphones, Facebook, Whatsapp, Flipkart, eating out all the time – change is everywhere. The serials promised predictability – old values, fractious families and mothers whose word was law. In a world with too much progress, there was a peculiar pleasure in their regressive-ness where everyone knew their place.

As much as my mother railed at their glacial pace and absurd twists and threatened never to watch it again, there was comfort in realising that the wicked mother-in-law would never quite be able to get rid of the saintly daughter-in-law even if she poisoned the milk or hired goons in Bangkok. There was reassurance in knowing that even after so many serials, Mejo-bouma had not figured out a better way to ruin Chhoto-bouma’s reputation than switching the sugar with the salt while she was cooking. And if the evil wife got too evil, my mother could mute her with relish until she had finished her rant.

But who could not warm to a serial where one character would tell another “Kintu aar maachhey toh kaanta hoy na (But aar fish has no bones)”? That is not technically true. Aar fish does have bones, just big ones, easily removed. But only in a Bengali soap would one character say that to another so knowingly.

Their homely predictability is their secret charm. In a world where no one had time for you anymore, the good people of the serial showed up without fail everyday with all the gossip about illegitimate children and thwarted love. Even your own children could not be counted on to be so conscientious. And best of all, you knew that in the end good would triumph and evil would get its comeuppance. That was non-negotiable. In these capricious times, that’s reassuring even if you have to wait 1,263 episodes for it.

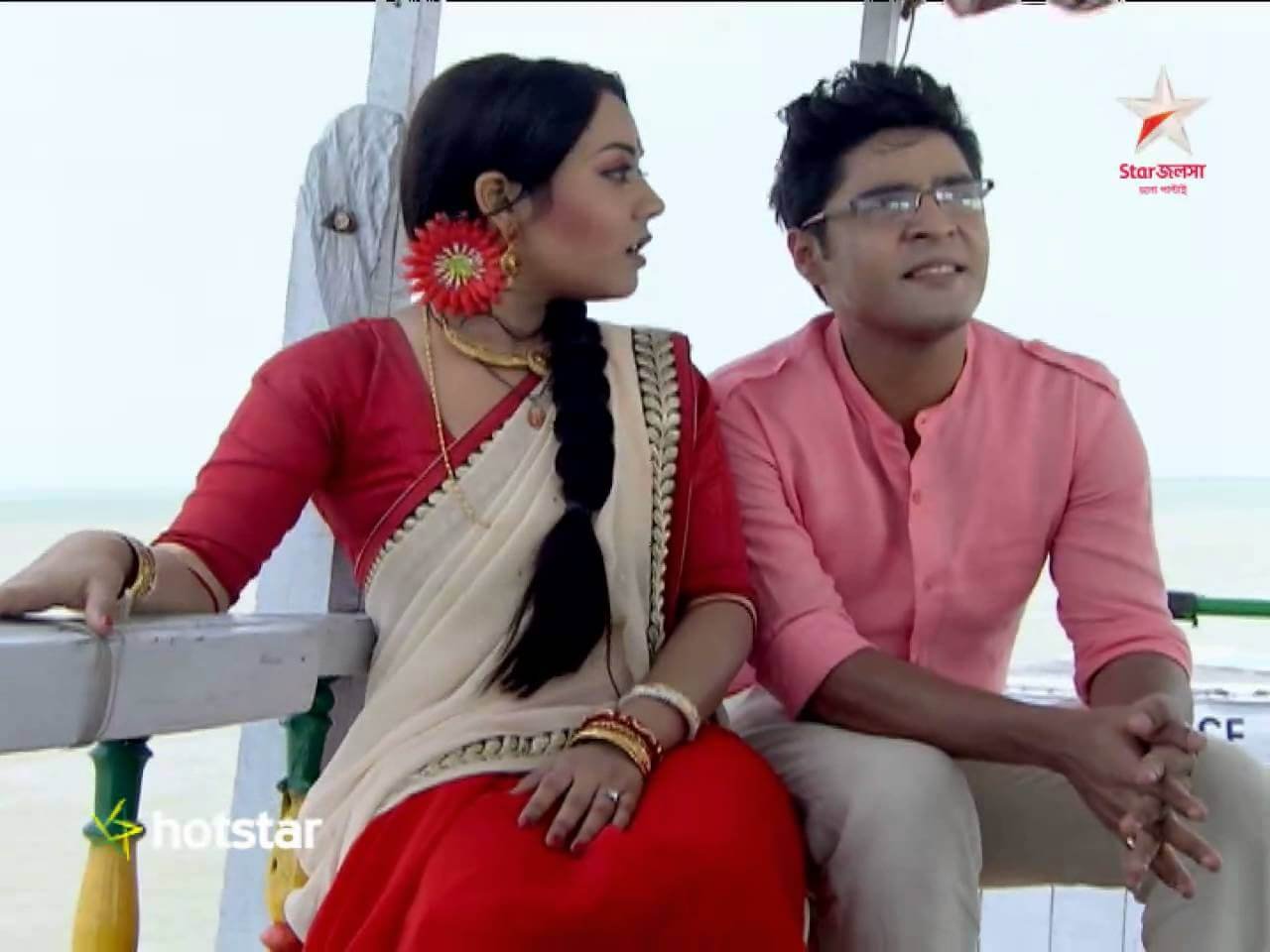

(Feature image source: Youtube/starjalshaindia)