On August 4, BJP workers filed an FIR against Neha Dixit, Krishna Prasad and Indranil Roy.

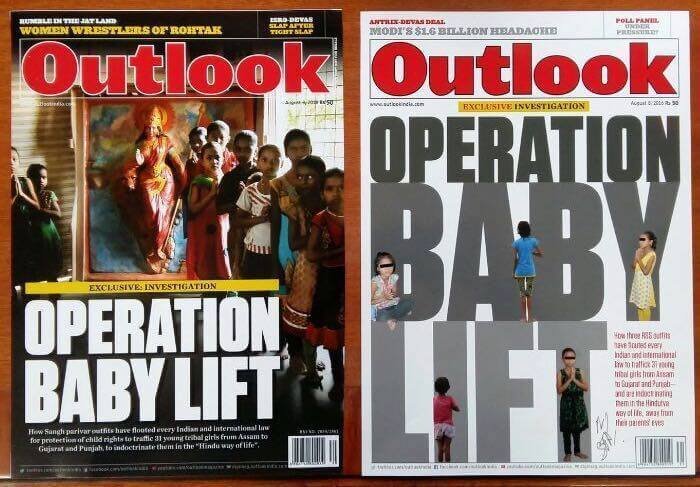

Dixit had written an 11,350 word investigative story about Sangh Parivar organisations flouting Indian and international laws on child rights and taking 31 young girls from tribal families in Assam to Punjab and Gujarat to “Hinduise” them. Outlook magazine had published the story. Prasad was the editor of Outlook (at the time), Roy the publisher.

The state government could have investigated the allegations and said they were baseless. But instead, an FIR was filed by BJP officeholders and the Assam Assistant Solicitor General for promoting enmity among different groups on grounds of religion

Then, on August 13, Indranil Roy sent an email to his staff saying they would have a new editor-in-chief from August 16. It requested them to welcome the new editor and extend their full support.

Outlook insists the change was long in the works and was not related to the RSS-exposé.

“It could be coincidental but definitely the timing of the announcement is shocking”, says Neha Dixit. “And the exit, unceremonious.”

The email from Roy did not mention Krishna Prasad at all, not even the pro forma expression of gratitude for his service. He had been Outlook’s editor since 2008.

Dixit is keeping her fingers crossed. As far as she is concerned, they are all still moving together to quash the FIR.

But the strange case of Neha Dixit and the #OperationBetiUthao story keeps getting stranger.

Dixit is no stranger to hot potato stories. She has written investigative reports and articles on the Muzaffarnagar riots, Naxalites and now the RSS. When she started working on this story which took her all the way from remote villages in Assam to Gujarat, she knew there would be a pushback.

There has been the official response. Priti Gandhi, member of the BJP Mahila Morcha National Executive published an open letter questioning Dixit’s “fear mongering and baseless assumptions”. Supreme Court advocate and Rashtra Sevika Samiti member Monika Arora wrote a blog saying Dixit’s “depraved mind” was conjuring up a criminality and seeing “the education of poor tribal girls in different states as ‘Trafficking’”.

There has been the social media response. An RSS pracharak emailed Dixit asking, “Even if it was illegal, do you think it’s immoral?” But other responses were about shutting down debate, not opening up discourse. Priti Gandhi signed off her op-ed with “No hard feelings!” – but on Twitter advised “a tight slap” on Dixit’s face. Pictures of Dixit and a man popped up on Twitter asking what that “Commie Naxalite” was doing “in her bedroom”. That man is her husband. And this is a journalist who has risked her life doing stories on child soldiers being used by Naxalites.

“But that level of stalking got to me”, admits Dixit.

And then there has been the media response. The Committee for Protection of Journalists has put out a statement condemning the intimidation as has the Delhi Union of Journalists and the Network of Women in Media.

“But I don’t know if many mainstream media organisations have picked it up or even debated the story”, says Dixit. “I expected everything the RSS and BJP has done. But not this.”

Dixit’s findings do not have to be taken at face value, but when stories are not followed up and debated, the story dies. What does it say about the state of our media that a single tweet that was essentially an off-the-cuff opinion by Shobhaa De on the Olympics seems to merit more debate and attention than an in-depth five-part story based on reportage, documents and court rulings?

The consequence of all this is that the Operation Baby Lift story is now about everything but Operation Baby Lift itself and whether it broke any laws. It has become a freedom of expression issue, about a reporter’s right to lay out the facts without fear and intimidation from some political-corporate nexus. The FIR makes it a story about that vague charge of promoting enmity between religious groups. And the BJP/RSS rebuttals make it a story about terminology.

Monika Arora quotes the dictionary definition of “trafficking” at her and says – “by your standards all parents who send their children to study in hostels in different states are traffickers, as are the institutions that accept and educate them”.

Priti Gandhi asks her for the definition of “Hinduise” and wonders whether the terms “Islamise” or “Christianise” are used when talking about madrassas and convent schools.

“We have become the story”, says Dixit. “It has completely deflected attention from the real issue.”

Dixit stresses that she is not the one who came up with the word “trafficking” to describe Operation Babylift. The Assam State Commission for Protection of Child Rights called it that in a letter it sent to the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights in 2015. Trafficking is about the process by which someone is recruited and transported, whether through coercion, fraud or deception. Trafficking is not limited only to instances when the child ends up in a brothel or as a maid in someone’s home or in a begging ring.

The issue is not that the children have been sent to hostels. The issue is that the parents have not been allowed to be in touch with them. Many do not have report cards or documents to prove they are in school. In Dixit’s story, both RSS worker Mangal Mardi and landless Santhal labourer Adha Hasda have sent their daughters to a school in Gujarat.

“But now he says (my daughter) is in Punjab and will not come back for the next four years”, says Adha. He asks Mardi – “How come you can speak to your daughter on the phone every day and I have not been able to do that for a year?”

That is the question that hangs over the story and remains unanswered.

As for Hinduise versus Islamise or Christianise, Dixit says the 2010 Supreme Court order she cites in the story came after a probe of trafficking of 76 children, mostly minor girls from Assam and Manipur to “homes” run by Christian missionaries in Tamil Nadu. No one is objecting to the use of the word “trafficking” in that order.

The government’s strategy is quite clear. They attack the integrity and motivations of Dixit rather than rebut the facts of the story. This happens over and over again. When the sting videos of Trinamool politicians allegedly accepting cash surfaced, the story became not about bribes, but about the Dubai-based motivations of those who made the video and the timing of its release.

Dixit knows doing these kind of stories come with considerable risk. When she covered child soldiers being used by Naxalites, she was in the forest for four days and no one could reach her. When she did the Beti Uthao story, she was trapped inside the Shishu Mandir and the gate was locked.

“When you work on these stories, there is always a degree of unpredictability”, she says. “The difference here is institutionalised bodies are creating this atmosphere for anyone doing an audit (investigation). If I say I’ll call the cops, they say go ahead, call the cops.”

It’s all the more frightening when that institution is the government which has all the power at its disposal.

No one is objecting to Monika Arora’s right to write a rebuttal to Neha Dixit. Outlook even published the rebuttal. But when journalism bodies do not pro-actively support Dixit in her fight to tell the story, the space for such stories shrinks automatically, even in India’s so-called vibrant and bustling media market.

Look around at the media landscape. How many places are left with the resources and the spine to do an 11,350-word investigative story like this? Soon, all we will have left in the name of investigation is a probe into why Hrithik Roshan is getting divorced, and that suits the powers that be perfectly fine.

The FIR against Outlook does not just come from random aggrieved RSS members. The complainants include a BJP spokesperson and the Assistant Solicitor General. It thus carries the official seal of approval of the state government. It is really a warning to any other publication that considers doing any such story that can ruffle powerful feathers. Dixit at least got to pitch the story and report it.

What you head towards is self-censorship, a story that is killed in the newsroom long before it can ever face an FIR. Or the story that never even gets pitched in the newsroom. And once there is no on-the-ground investigative report, there will be no facts to debate, just opinions to hurl in television debates. And the transformation of news into infotainment will be complete.

Where does that leave a freelancer like Dixit?

“One is always alone in this. I became a freelancer because I realised there are a lot of stories I cannot publish within one organisation”, says Dixit. “But now I just don’t know. Personally all I am trying to do right now is not miss another deadline.”

Feature Image Source: Facebook