Some stereotypes do ring true. Yesterday, my non-resident Kolkatan friend from Philadelphia called me bang in the middle of the day. It must have been the witching hour there.

“Eta ki hochche?” (What on earth is this), he hissed. “West Bengal ekhon theke Bongo (West Bengal is Bongo from now on)?” he asked.

Mamata Banerjee had made her presence felt across continents, it seems.

The West Bengal state cabinet has decided to drop the West from West Bengal in English and rechristen the state as Banga (pronounced: bongo) in Bengali and Bengal in English – and Bengalis from Patna to Pittsburgh choked on their frozen hilsas. Kolkata, (formerly Calcutta and probable Uttam city) remained unfazed, thank you.

We don’t care anymore if our flyovers are called “Maa” (Mother), our streets are renamed Satyajit Ray Dharani (roughly translated as Satyajit Ray earth) or our Metro stations are named after Tollywood superstars (Mahanayak Uttam Kumar). Let Mamata Banerjee have a field day renaming everything Bengali, as she has in the past five years. She has earned her right to do so with an overwhelming majority. We have more mundane things to worry about. Like how not to be crushed by a flyover at peak traffic hour.

“What difference will that make?”, I cooed soothingly. Will the Nahoum’s brownie or Ghosh’s peanut alu-filled shingara (what the less civilised call samosa) taste any different when you come here for your yearly visits,” I reasoned.

“No, we are not Bangla or Bongo. We are West Bengal. To do away with the ‘West’ is to do away with history. The West reminds us of the scars of history and how we shouldn’t repeat past mistakes!”, he thundered.

What is it about this name change that has made non-resident Bengalis react so passionately?

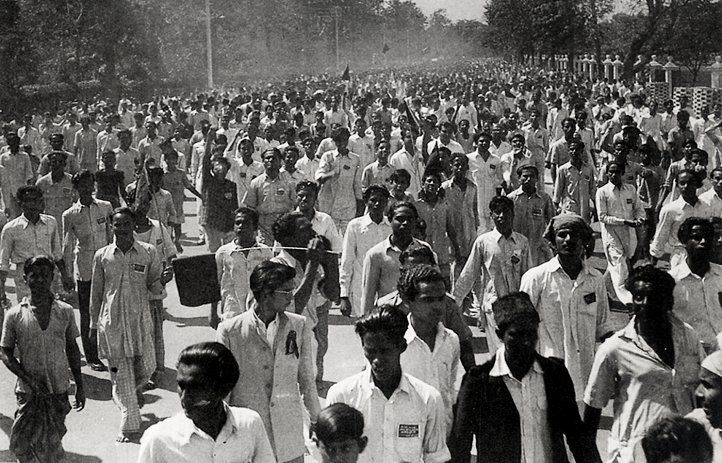

To answer the question, we need to understand the significance of “West” in West Bengal. For millions of Bengalis around the world, it means something personal. The Partition of Bengal in 1947 – the second time Bengal was partitioned on the basis of religion after the first unsuccessful attempt in 1905 – divided the province of Bengal between India and Pakistan. Predominantly Hindu, West Bengal became a province of India. The predominantly Muslim East Bengal (now Bangladesh) became a province of Pakistan. Millions of Bengalis from both sides of the border migrated leaving behind their homes, friends and roots.

Ask any Bengali from anywhere and he or she will have some partition story to share. Many of us have grandfathers who were zamindars of some obscure province of Bangladesh. And grandmothers who got misty-eyed while talking about their ancestral homes in Pabna, Chittagong or Sylhet. The fish was tastier there, the rosogolla (which the Oriya are trying to usurp, but we Bongs know better) was spongier and even the water sweeter. Bangladesh is our Jerusalem.

Little wonder then that the terms “East Bengal” and “West Bengal” were meant to be a reminder of a time when both these Bengals were one. However, East Bengal ceased to be East after the liberation war of 1971. West remained West. Many feel that holding on to a painful memory is unnecessarily sentimental.

“The partition is just not a historical event for us Bengalis. Many people lost their homes, their motherland because of it. It’s a part of their lives, their lives have been shaped because of that particular event. For them, the term West in West Bengal denotes a sense of pain,” says filmmaker Pradipta Bhattacharya.

However, for many Bengalis, such as myself, West Bengal is the only Bengal we know. We may have relatives or grandparents who have a connection with erstwhile East Bengal, but we have no emotion whatsoever attached with the Eastern part. We feel thwarted when we see that Bangladesh has ceased to be East Bengal, while we have held on to the memory like we have Stockholm Syndrome.

Ask any first generation migrant, and he or she will tell you about the horrors of the partition. There are many who migrated during the 1970s and they have their own stories too.

“It’s unfair for us to romanticise a dreadful event that we have not seen or experienced”, says Dipak Chatterjee, a cadre with the CPI-M in Kolkata.

Clearly the West Bengal, sorry Bengal, government feels the same.

“It’s a need of the time to respect the culture, heritage and aspiration of the people of Bengal”, said state minister Partha Chatterjee while announcing the Cabinet decision.

You can’t really argue with him.

Featured Image: Wikimedia Commons/ Biswarup Ganguly