Here is an excerpt from the book Military Inc. by Ayesha Siddiqa published by Penguin RandomHouse. In this excerpt, Siddiqa tries to explain the complex love-hate relationship between Pakistan military and India.

The country’s policy-making elite tends to define threats to national security mainly in terms of the perceived peril from New Delhi.

India’s hegemonic policies and belligerent attitude are considered to be the greatest threat to the survival of the state. Over the past 50 years and more, the dominant school of thought that has influenced policy making believes that the Indian leadership has never been comfortable with an independent homeland for the Muslims, and would not lose any opportunity to destroy or invade Pakistan.

Policy makers are equally uncomfortable with India’s urge to gain regional or global prominence. Any reference to India acquiring a prominent role, especially as a result of its comparatively greater military capacity, is seen as a potential threat and as inherently antithetical to Pakistan’s security interests.

This first war with the neighbouring state in 1947–48 established the primacy of the national security agenda. From then onwards, military security was given maximum priority, resulting in the government allocating about 70 per cent of the estimated budget in the first year for defence.

This budgetary allocation symbolized the prioritization of the state and national agenda. According to Hussain Haqqani, a research fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, after the first war, ‘“Islamic Pakistan” was defining itself through the prism of resistance to “Hindu India.”

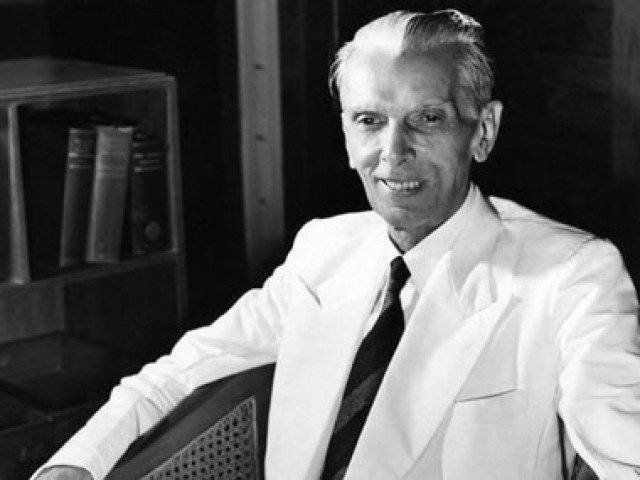

The Indian threat had an immediate effect in making the military more prominent than all other domestic players. This development was accompanied by lax control of the management of the armed forces by the civilian leadership. In fact, the founding father was unable to take firm control of the armed forces during the early days. Mohammad Ali Jinnah could not even enforce his decision to deploy troops in Kashmir.

General Gracey, the Pakistan Army’s commander-in-chief, expressed a reluctance to obey Jinnah during the 1947–48 war for which he was not admonished. However, a prominent Pakistani historian, Ayesha Jalal, claims that the military did not resist its orders, but Jinnah was convinced to change his earlier decision to deploy troops in Kashmir by General Auchinleck, the joint commander-in-chief for India and Pakistan.

In contrast, Cohen holds the founding father responsible for lax control over the army by leaving ultimate strategic military decision making to General Gracey. 21 In any case, the war opened a Pandora’s box by defining Pakistan as a state that viewed its existence from the perspective of its hostile relations with India.

Brig. (ret.) A. R. Siddiqui is of the view that ‘the use of tribals that had gone into Kashmir to take control of the Kashmir valley led to the war, thus sealing the fate of Kashmir and turning Pakistan into a military-dominated state’.

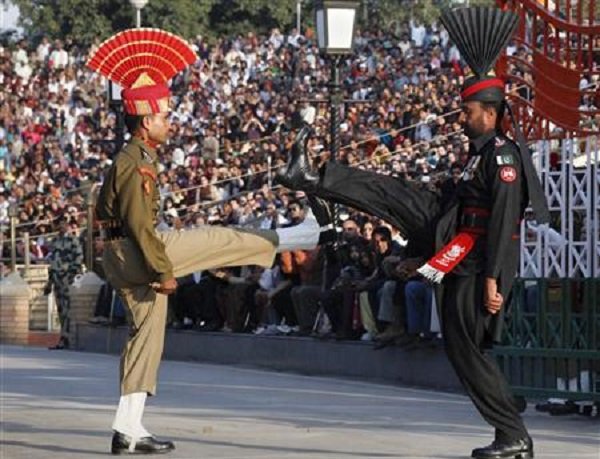

Since this first military conflict, Pakistan has fought two-and-a-half further wars with India over the unsettled dispute about Kashmir. The military establishment and the policy-making elite view the issue as critical for Pakistan’s security. In the words of Pakistan’s president and army chief, General Pervez Musharraf, ‘Kashmir runs in our [Pakistanis’] blood.

However, the issue is part of a larger perception of India as being inherently hostile to Pakistan. Military leaders such as Musharraf believe that the end of the Kashmir dispute might not necessarily result in a complete easing of the tension with India, so despite the post-2004 peace overtures with India, there is no fundamental change in the military’s thinking regarding a possibility of friendship with the traditional foe.

Perhaps more importantly, the military also tends to see internal security issues and domestic political crises as extensions of the larger external threat. The rise in ethnic and sectarian violence in the country is a development that can be attributed to the covert and nefarious activities of India’s intelligence agencies.

There is a popular notion that unless they were provoked and funded by external actors, especially New Delhi, the various ethnic and sectarian groups would not be able to cause violence in the country. This perspective is challenged by Hussain Haqqani and Hassan Abbas, who explain the rise in ethnic and religious violence as a result of the military’s policies.

Religious extremists, and the religious and ethnic parties in general, are allowed to play a greater role in support of the defence establishment’s national security objectives. The military allowed the religious parties to produce the necessary personnel for deployment on any front where help was needed.

The discussion of national security as determining the army’s utility for the state also serves as a reminder of the primacy of the military’s corporate interests, which play a significant role in the formulation of state policies.

Just like in India, little attention is paid to erroneous policy making and bad governance, which is directly responsible for domestic unrest and sociopolitical fragmentation. Since the military has acquired the role of the guardian of the country’s sovereignty and overall security, the organization tends to view domestic political crises from the perspective of the external threat.

Similarly, the military looks at internal crises such as the problems in Baluchistan, Sindh (during the 1980s), or in the tribal areas bordering on Afghanistan, as the results of India’s hobnobbing with the miscreants in Pakistan.

Security against India, it must be reiterated, is the raison d’être of the armed forces. Hence, the military leadership and the overall Pakistani establishment consider it essential to strengthen the military, and view a possible reaction primarily from a classical realist perspective.

All forms of interaction with Pakistan’s larger neighbour, including cultural links and trade and commerce, are seen from the standpoint of national security.