In 2013, ISRO put India’s Mars mission on the map by launching Asia’s first Mars Orbiter, Mangalyaan. Behind its massive success, was a team of several brilliant and accomplished women scientists who spearheaded our Mars space program into fruition. The mission was formally called M.O.M. (Mars Orbiter Mission) perhaps to pay homage to the team of trailblazing women behind it.

6 years later, Bollywood is adapting their story into an upcoming film about the entire team. The film, Mission Mangal has a stellar cast of women who can convincingly play ISRO scientists and follows the story in a dramatic retelling. And it’s great that their efforts are being recognised by mainstream Bollywood.

However, what is irksome is that Bollywood continues to uphold the one-man-army cis-gendered male saviour hero trope even in a story where women did a lot of heavy lifting.

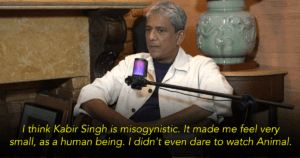

When we first heard about Mission Mangal, we were ecstatic assuming it was going to be all about them or at least about both the men and women in equal measure. When we saw the trailer, however, it was less than heartening to see how the women were reduced to characters full of self-doubt and apprehension about their literal job. Amidst these women emerges the unstoppable male hero with an I-can-conquer-the-world attitude, in the form of Akshay Kumar — Bollywood’s go-to man-saviour — talking down on all of them and telling them how it’s totally possible.

While Bollywood has come a long way when it comes to treatment of female characters in film, it has a lot to learn about its default hierarchal approach given to men over women. It’s also notable that not only is Akshay Kumar’s character given a much bigger role than his real-life counterpart, it also changed his background to North Indian, for no apparent reason.

This is not the first time Bollywood took special efforts to glorify the women’s maseeha and give him the relentless saviour complex. Take for instance these films.

Padman and the ‘sanitisation’ of caste and gender hierarchy.

In Padman, our prized hero complex victim, Akshay Kumar reprises his role as mahilaaon ka rakshak. In a film about menstruation, a cartoonishly positive Laxmikant takes it upon himself to end the period taboo and stigma. While his real-life counterpart, Arunachalam’s efforts are commendable to say the least, the film does zilch to reflect the magnitude of social ostracisation he had to endure for belonging to a lower-caste and socially backward strata.

Instead the film continues to make him the hero, upholds him as the one who puts ‘man’ in wo’man’ and ‘men’ in ‘men’struation, and makes him the only person who recognises a problem women have literally been complaining about since the dawn of time. I wouldn’t be surprised if the next thing we see is a film where Akshay Kumar does another man-saviour where he’s the only one who somehow realises that women need pockets and starts manufacturing it for them.

Pink and the need for a man to certify a woman’s truth.

Another irksome rendition of ‘feminist’ storytelling is the bold Taaspsee Pannu starrer Pink. Credit where it’s due, the film did a fabulous job of opening up a dialogue about consent and crimes against women. It, however, failed miserably in the representation department as the film starts sprinting into a positive conclusion only once Amitabh Bachchan fully enters the frame.

Not only does he have the maximum dialogues in the film, his entry also marks the film’s turning point where the women actually start being taken seriously. He is the messiah who rescues the damsels out of their distress. And only when he repeats their testaments in his signature baritone, do the authorities even lend an ear to the women.

His presence throughout begs the question: Why did we need a man to lead the way in a film about women?

Chak De India and a man taming a group of unruly women.

Next, we move on to to a cult sports film. It was a breath of fresh air to see the focus shift to women in sports with Chak De India. And the nuance with which it modelled each character was remarkable for a Bollywood film.

While it was truly a leap forward, this film too fell into the same old male-saviour trope. In a film about phenomenal women in sport, the only character who got a fleshed-out backstory was the team’s male coach. He’s the only one who has regular flashbacks and the most fulfilling character arc of them all.

It is telling, when a film that celebrates a women’s hockey team gives most precedence to its sole male character.

Dangal and the man’s mission to make men out of women.

Another instance is the similarly modelled Dangal. While the film is supposed to follow the phenomenal journey of women wrestlers from the regressive state of Haryana, Dangal ultimately boils down to the man of the film. Not to take away from Mahavir Singh Phogat’s relentless pursuit of turning his daughters into sports stars and the brilliant cinema that Dangal is. But the film is essentially constructed on the massive power of the male ego.

The question still remains. Why do we assign a certain value to the male character in the film? Even in films which celebrate women, a certain primacy is given to the male character.

Although it’s not all bad in B-town. The occasional brilliance does come in the form of a Queen, English Vinglish, or Nil Battey Sannata, where women can handle the plot without a man’s training wheel. While we’re not asking for these to be the norm. All we want is for a film to at least not have a man swoop in and save the day when it is absolutely not necessary.

When a film is about women, let it be just about the women, maybe?