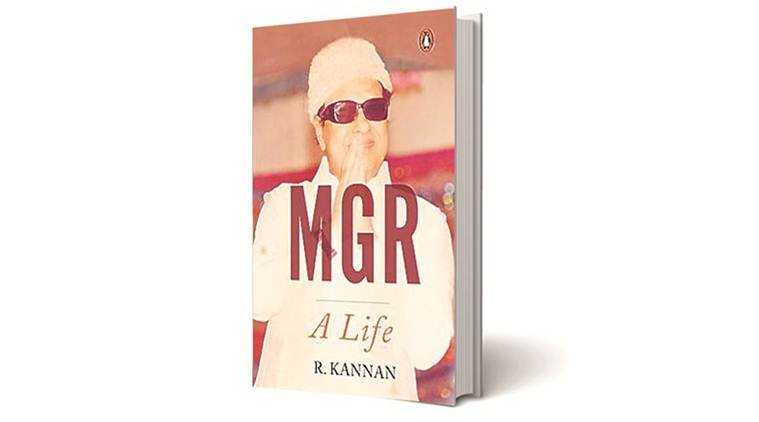

MGR, a name that defines Tamil Nadu politics and its cult of star-turned-actors. MG Ramachandran, the AIADMK founder, led a life that would make for a perfect potboiler. Which is why it’s not surprising that author R Kannan has published a biography on him. MGR: A Life (Penguin) is the story of the actor’s struggle from poverty to superstardom as it is a history of the Dravidian movement and Kollywood.

Here is an excerpt from the biography which focuses on MGR’s tumultuous relationship with Jayalalithaa.

On 4 June 1982, Jayalalithaa enrolled as a party member. S. Ramachandran recalled that ‘nobody’ wanted her in the party. But MGR did and that was enough. In 1984, in what might be the most authentic version of the sequence of events that led her to entry into the AIADMK, she told Ananda Vikatan how she took to public life: I told Mr MGR that I wished to engage in politics. ‘Do not be hasty . . . You have to read a lot,’ he said. I have been interested in politics and have been observing developments. I showed more interest. In 1982, I again told Mr MGR of my wish. He gave me a book containing [the] AIADMK’s principles, asking me to read it carefully. Two months after this, I joined the AIADMK.

As someone who had read politics, there is no doubt that MGR had caught my attention. But, that is not the only reason . . .Gandhiji spoke of a village raj.

Thirty-six years after Independence, no administration has helped the rural folk as [much as] MGR’s administration has. In north India, there are villages where people cannot live because there is no water. Here, MGR had introduced a self-sufficiency water scheme . . . Now free nutritious meal scheme . . . The Centre is not helping a bit with these. They say MGR’s administrative ability is inadequate. Which chief minister claiming administrative competence has been able to bring such schemes? Who stopped them? When even Congress [I] chief ministers did not care about Gandhiji’s rural raj, these feats of MGR attracted me!

In 1999 she said she entered politics for his sake.

I entered politics because of the influence of my political mentor, Mr MGR. I really came into politics just to be of help to him.

Because he said he could not trust the people around him, and, at that time, his health was beginning to fail, and he wanted someone whom he could trust 100 per cent, someone who he thought could be totally dependable and reliable. I really came into politics just to be of assistance and help to him. But then both Jayalalithaa and MGR had come full circle. MGR needed her charisma, competence and crowd-pulling skills. He had pointed to her reading habits, her English, her potential to draw crowds and wondered to S. Ramachandran, ‘Why can’t we utilize her?’ He had once sought to ‘own’ her and she had freed herself. And now she was back after a tumultuous personal life and a film career that was behind her. And this time, ironically, she would ask for all the attention and often not get it, mostly because of her own doing. She had declared in 1984 that she would be his ‘most loyal’ follower. But ‘MGR felt that she often crossed the line,’ said S. Ramachandran. But her loyalty to MGR itself would become suspect.

Time has shown that Jayalalithaa’s entry into the party would prove a mixed blessing. While Jayalalithaa consolidated MGR’s electoral legacy, she must have also made him turn in his grave daily— for pushing his memory completely into the background, turning into a megalomaniac, naming everything after herself, and perhaps also for being the only chief minister who had to quit office twice on charges of corruption. For a woman who was his heir and who claimed to carry his agenda forward, she would visit MGR’s home in Ramavaram Gardens only after two decades, in 2010, when actor Vijayakanth posed a threat, laying claim to MGR’s mantle.The fact that MGR did not identify her as his successor till the end speaks volumes of his ambivalence towards her.

Su. Thirunavukkarasar acknowledged that MGR would suggest Jayalalithaa conduct public meetings, instead of him, as his health was not good. But P.C. Ganesan, one of her biographers, says that even MGR’s files were sent to her ‘for comments’. Solai was given the task to train her in public speaking and to write her speeches. Valampuri John appears to have also assisted with her speeches. Solai recalled her reading the first speech he had prepared and repeating it on her request thrice. Solai was astonished when she was able to repeat the speech verbatim.

Her debut speech was not political. MGR had asked her to give a talk on the ‘Greatness of Women’ at the Cuddalore party conference that year. But she turned it into a political speech, when she rhetorically posed the question: ‘I am asking you; you tell me, aren’t you all on the side of Puratchi Thalaivar MGR?’ The crowd roared a ‘yes’ then.

MGR seemed both possessive and eager to flaunt the star as a trophy. Equally, Jayalalithaa proved too impatient and eager to come out of MGR’s shadow. Her independence, bordering on disobedience and disrespect to MGR, led to their relationship blowing hot and cold by turn, and her detractors taking advantage of her shortcomings to widen the chasm between the mentor and the mentee. But she always managed to climb back into his good books and take advantage of MGR’s fascination for her. Her detractors like Valampuri John alleged that MGR was ‘suspicious’ and monitored Jayalalithaa’s every move. It is not clear if MGR was suspicious, protective, possessive or a control freak. Salem Kannan too would have us believe that MGR watched her. S. Ramachandran said that MGR monitored the size of her meetings, the reception and the content of her speeches.

It is true that Jayalalithaa had to take instructions and approval for her activities. But she took her job seriously. She was given the green light then to attend the party office and go on a tour once in ten days. Her debut political meeting on 17 October 1982 happened at Mangollai, in Mylapore, Madras. She criticized the Centre for not involving itself in the Cauvery issue because of the elections in Karnataka. She also said that if Karnataka were to claim ownership of the Cauvery water then a situation would arise where Tamil Nadu might claim ownership for the oil discovered on its shores.That day, MGR met Indira Gandhi in a one-to- one meeting in Delhi for twenty minutes, among others, seeking her intercession for the release of 2600 crore cubic feet of Cauvery water, and the prime minister had said that ‘she wanted to help’. Ananda Vikatan reported that there was a heavy police presence around the meeting venue and policemen locked arms to form a human chain, preventing entry even to residents of the street where the meeting was held. Jayalalithaa wore black blouse and a dark red silk sari, and spoke last of all, with notes. Sometimes, when she tried to raise her voice to pose a challenge to the Opposition, it sounded muffled because of its femininity.

She enlisted the measures to tackle the difficult water situation in the state, and her speech was full of statistics and data. Some police officials were seen taking notes.

Others recorded her speech. At the end of the meeting, it began to pour outside. ‘Anni (elder brother’s wife) Jayalalithaa and the rain have come, see!’ a woman flower vendor outside said, holding up the garland that Jayalalithaa had given her.

On 23 November, the media would carry a picture of the chief minister flanked by his wife to the left and Jayalalithaa to his right, watching the ASIAD in Delhi, highlighting the chief minister’s wish to exhibit her as an equal to his wife.*

In 2008, Jayalalithaa said that MGR had asked her to promise that she would never leave the cadre, whatever the hardships they faced, hinting that he wanted her to lead the AIADMK. On 16 October 2012, on the forty-first anniversary of the founding of the AIADMK, she issued a statement in which she said: MGR’s appeal was that I dedicate my life to protect his followers.

He obtained a vow to this effect from me . . . To protect you, the Kazhagam’s siblings, I have dedicated my life to the Kazhagam and you. To be in Tamil Nadu’s political life as a woman is not an easy task. This is a river of fire. It is a script of ingrates, full of deceit and intrigue. Yet, I understood at the very beginning that I should not abandon my duty fearing these.

But one ‘sibling in spirit’ would become dear, from 1982, and Jayalalithaa would protect her until the end. Civil servant Chandralekha introduced Sasikala Natarajan, a video rental and filming facility owner, soon to become the ‘sister that I have never had’ to Jayalalithaa, in 1982, during the centenary celebrations of poet Subramania Bharati. Sasikala’s husband, M. Natarajan, a public relations officer, who was not yet estranged from his wife, worked with Chandralekha. ‘Jayalalithaa’s programmes were covered by Sasikala’s team . . . Through that some good association developed,’ M. Natarajan would say, in an understatement later.