“Sport is an athletic activity, not a religion or a ritual. It’s not about life or death. It needs to be natural, light, free, healthy and humane.”

— Martin Crowe in Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack, 2014.

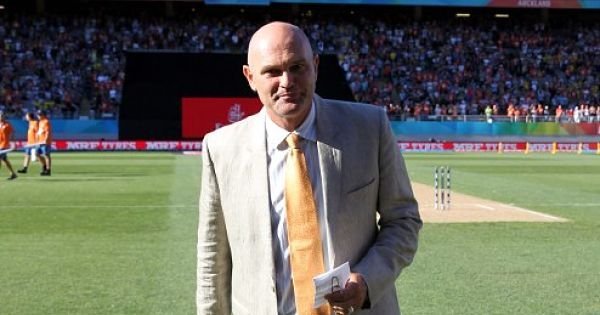

Those words defined Martin Crowe the batsman and the person. His batting contained pure joy, his approach to the game was reverential and light-hearted and his attitude towards life was zestful. The memory that will linger forever in the mind, though, will be of Crowe as a batsman.

It is easy to get attracted to style when you are a child. And Crowe had spades of it. A white panama hat or a bandana under a helmet, sleeves buttoned up till the wrists and a big frame moving lithely and elegantly at the crease. His elegance was more of the measured kind – minimum backlift and a whip of wrists that couriered the ball powerfully to the fence.

The earliest sighting of Crowe was through the occasional grainy clippings that Doordarshan would air in the mid 80s. It was hard not to notice the stylish batsmanship of Crowe even in those tiny seconds often accompanied by a ludicrously loud background score.

Then came the 1992 World Cup. A tournament that cemented Crowe’s status as one the game’s greats. He batted with verve and captained with imagination. Don’t forget it, the 90s was the age of fast bowlers – Wasim Akram, Imran Khan, Kapil Dev, Richard Hadlee, Curtly Ambrose, Courtney Walsh, Allan Donald; they came in plenty during those days.

But Crowe gave a rude shock to the conventional wisdom by handing the new ball to off-spinner Dipak Patel. The move paid off handsomely, forcing the opposition to think differently and revisit the strategy of their openers. Crowe sparkled as a batsman too. Akram, Imran, Malcolm Marshal, all the leading pacers got to know the heat of Crowe’s bat. But then a delicate knee soon ended Crowe’s topflight cricket career at 33.

However, Crowe was not lost to the cricketing world. He grew as an astute thinker of the game, imparting his knowledge and thoughts as a commentator. As a mentor, Crowe ensured that Ross Taylor was not lost to New Zealand cricket, helping the right-hander tide over a tough phase.

Sad to hear about the passing of NZ cricketing legend, Martin Crowe. A fine captain and exciting batsmen. RIP, sir. pic.twitter.com/GvPuSx1JRx

— Thomas Falkiner (@TomFalkiner111) March 3, 2016

Crowe had a brief association with India too when he coached the Royal Challengers Bangalore in the inaugural edition of the Indian Premier League. It was not a very successful stint as Royal Challengers finished at the bottom of the ladder, but Crowe never let the frustration boiled over. I had a chance to conduct a brief interview with Crowe in 2008, and one of the questions was on his motivation to take up a coaching role in T20, then a rather unfamiliar format. He replied with a laughter: “Fresh challenges needed to be tackled head on, than shy away from it for the simple reason of not having done it before.”

Certainly, Crowe would not have foreseen lymphoma would conquer his body four years later. But his words were almost prophetic. He faced the challenge of a terminal illness with composure, and never let it touch his spirit which was insurmountable. In fact, he became one of the most eloquent writers on the game in his last passage. He was quite the wordsmith – combining grace, command over language and his deep knowledge of the sport to perfection. His articles on ESPNCricinfo were pleasant reads and thought-provoking at once. Not many had managed that twin feat like Crowe did.

He was leading a full-throttle life despite knowing that the end could not be too far. He never sounded despondent. Never cursed the fate. He was way too spirited for that. In that, he is a model for all of us – on how to tackle difficulties with a smile. His memory will always remain fresh.

Go well, Martin.

Feature image source: AFP