In 2019, a study noted that India has the lowest divorce rates in the world, with less than 1 per cent marriages ending in divorce. “1.36 million people in India are divorced. That is equivalent to 0.24% of the married population, and 0.11% of the total population,” the report stated. So only 13 out of every 1000 marriages in India were ending in divorce.

This statistical data is important for two reasons:

One: That the most recent data on divorce gender and society that we have is as dated as 2016 – this study was based on a 2016 BBC report – five years too late.

Let’s take for example, another study that puts India at the bottom of the happiness index and Finland at the top. Nearly 4 in 10 first marriages in the world’s happiest country end in divorce.

Am I trying to relate happiness to divorce rates? Not directly. What I’m trying to explain is that, stats and figures, aside, we are a country of unhappily married ever afters.

While countries like US and Luxembourg normalise getting out of an unhappy marriage and being divorced, in India, we’ve been taught to settle, adjust and stay put in a bad marriage, come what may. It’s like being told to colour within the lines but you can’t colour anymore.

Since 2016, the divorce rate in our country too would have increased, given the global rise in divorce rates. But, even then, we fall far behind. As pointed out by scholars at Bangalore’s Azim Premji University, “Although there is a lot of anecdotal evidence about ‘skyrocketing’ divorce rates in aggregate terms, we are not particularly high globally in terms of the rates of divorce.”

So, why are we as a society so afraid of divorce?

Almost all relationship experts and psychologists agree that the term still comes with loaded stigma. The modern Indian diaspora is still intimidated, or unequipped to deal with divorce. And, more often than not, it has little to do with the children born from a marriage, or the end of a relationship. But, it has more to do with the patriarchial idea of how a society should function, or how women in a society should be bound. That, and religion.

In the Bhagavad Gita, it is noted:

“Srila Prabhupada has said that only sudras divorce and remarry. A person with brahminical qualities are not expected to divorce and remarry. Because the woman he is going to marry again could have married another unmarried man. Even if he marries another woman who is also divorced, she is the wife of another man. Marrying the wife of another man is considered as adultery.”

And in the Bible, it says:

“But I say unto you, That whosoever shall put away his wife, saving. for the cause of fornication, causeth her to commit adultery: and. … and whoever marries a divorced woman commits adultery.”

— Matthew 5:32

In the Sikh community, divorce was not even a provision in the Anand Marriage Amendment Bill that was introduced in the Rajya Sabha in 2012.

We have turned the union of two people into a deal with deities simply so we as a society can continue to control the narrative of the adarsh bahu and the sanskaari family.

In May 1949, Roma Mehta wrote in the Economic Weekly, a respected journal of its time, “There can be no objection to the right of divorce. But conferring this right on women, by itself, would be unmeaning and probably more productive of harm than of good.”

These words may have been written in 1949, but even in 2021, popular familial dinner table discourse more often than not reflects this very ideology. The fact that this thought process comes from a woman is then, all the more heartbreaking.

She further went on to confer as to how Indian women were “more protected and much better cared for than in the West”; that they found “more happiness more often than not in her home; and her troubles and heartaches were solved in family” where she lived. “The incompatibility may sometimes be very great indeed; but in spite of it all, the family is maintained.”

Even today, when the hint of an unhappy marriage makes its presence felt, the general suggestion from parents, close friends and unwanted well-wishers is to ‘sort it out’.

Out of personal experience, it took my parents 7 years to finally come to terms with the fact that they could no longer live together under the same roof anymore, let alone be in a relationship. It then took them another 5 years to finally call it quits. I’ve had family members explain to the women of our household (more than the men) about how they have to adjust to make a marriage work, no matter how unhappy or mentally drained they were.

What about the kids?

What will the neighbours say?

What will society say?

What will men say to a divorced woman with kids to raise?

Where will you go if not back to your husband?

In each of these questions, the answers are almost always asked of the woman; not the man. In. Even today, we live in a society where for every discretion in a marriage, it’s the woman who is held accountable, not the man even if it’s his fault.

Words like ‘adjusting’, ‘compromise’, ‘settle’, ‘understand’ get thrown around more than they are actually understood.

Reality shows like Indian Matchmaking only further reiterate this sad truth that even in the 21st century, we want our women to be adjusting and compromising in a marriage.

Even popular Indian TV serials, add fuel to fire with sensational storylines that either victimise or glorify the women going through separation or divorce, instead of normalising it.

Case in point: There are currently at least 2 TV serial on air in our country – Anupamaa and Kyun Rishton Mein Katti Batti – with similar plotlines. The lead couple are on the verge of separation and divorce due to the indescretions of the husband. The separation is mutual. Yet, somehow, the family wants to get hem back together to the extent of going behind their backs and blindsiding the couple.

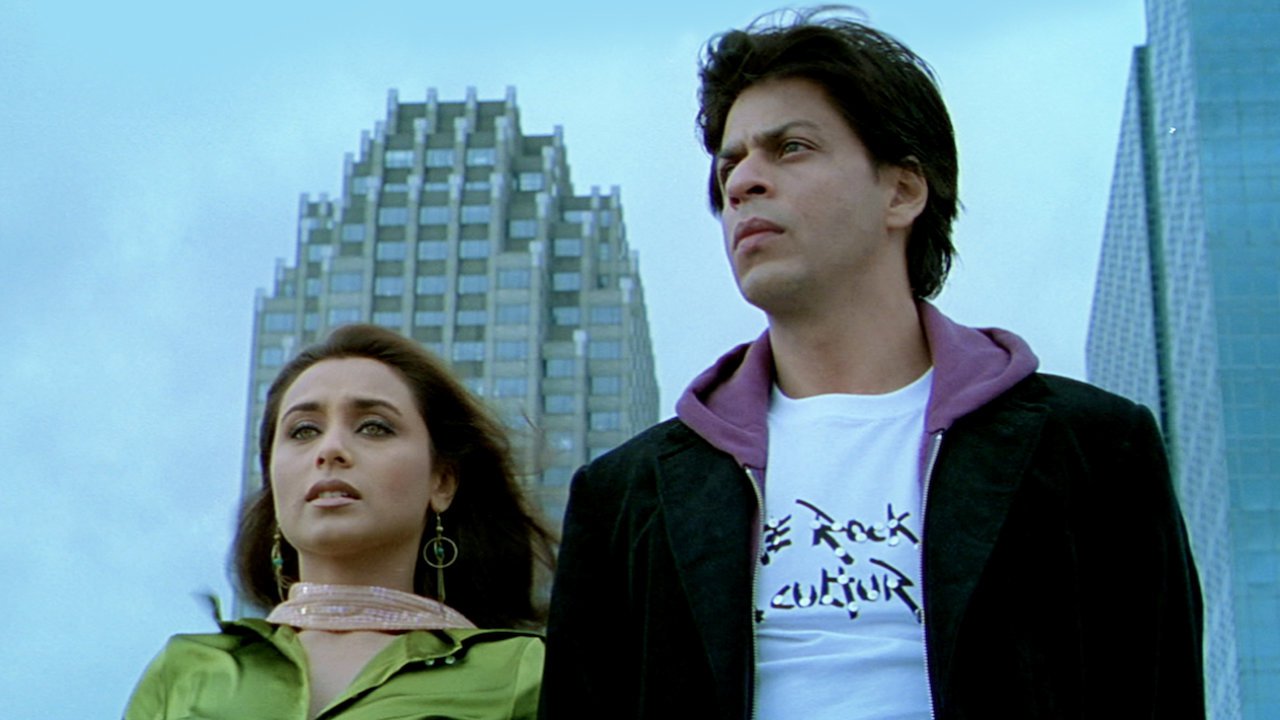

In fact, so tied are we to the idea of binding a marriage together that when Karan Johar’s Kabhie Alvida Naa Kehna released in 2006, it made Indians uncomfortable and was the reason why it didn’t become a KJo favourite the way K3G continues to be. Some said it was ‘way ahead of its times’ for simply portraying two unhappily married couples who found love outside of their marriages, came clean and divorced and lived happily ever after. We couldn’t handle the fact that the movie ended in every individual finding their own happy ending because we’re so used to tying them together.

Sure, Silsila portrayed infidelity, too. But, in the end, Amitabh and Rekha did the morally right thing; they went back to their spouses. In KANK, no one did ‘the right thing’.

Staying in a marriage, however unhappy, unhealthy and abusive it might be, is doing the right thing according to our society.

According to a 2018 NCRB report, Indian housewives accounted for the second largest number of deaths by suicide. Further details of the report revealed that these women were subject to domestic violence, dowry harassment and were made to live without basic necessities or human dignity. In 2019, the NCRB further recorded over one lakh complaints of domestic violence.

While couples counseling and marriage counselling are ideas that are still taking shape in India, even today, families trust couples to take their marital problems to the local priests, or the panchayats in their villages. And the general consensus is that being unhappy in a marriage is normal. The next solution to the issue is to have a child.

The heartbreaking truth is that Indian families would much rather grieve the death of their daughters-in-law than let two people divorce each other and live on peaceful terms, simply because they’re afraid ‘Log kya kahenge?‘.

It’s no wonder that divorce is still considered taboo and rather outlandish in conventional Indian society. For the same reason parents still want an arranged marriage for their children even if it means going against their will. Financial status, caste, social status, familial pride and prestige. We still want to portray to the outside world that, just like in Sooraj Barjatiya’s family drama, ‘Hum Saath Saath Hain’, despite the many loopholes.

We want to look morally right and just, even though our realities maybe so skewered and inching towards the immoralities that don’t get talked about because all is fair in family and marriage.

In our bid to build loving familial relationships we are forging ties that end up binding and gagging us. Because, even in 2021, when divorce has become a right equally granted to men and women, society would rather see a married unhappy couple than they would see two individuals who are happy alone.