As kids, it used to sound endearing when someone asked ‘Why did you have to walk on the edge?’ right after we had fallen. It was a sign of concern, however masked the blame was. Somehow, we were asking for it. We believed it as we wiped away the tears while the wound stung.

Then we grew up and those innocent counters were replaced with more serious ones.

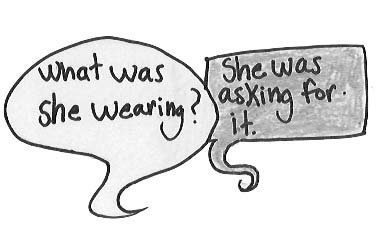

“Why did you have to stay out so late, or wear that short skirt, or smile at him?” was a retort to opening up about how we had been eve-teased, assaulted or raped.

Somehow, we’re still asking for it, despite the fact that we lock our doors and windows, carry pepper sprays and look sheepishly at a stranger who walks too close to us. Part of the reason why we do this is also to avoid the questions. So that it doesn’t come back to us. A bit of a Catch-22 situation, don’t you think?

That’s what victim blaming is.

We’ve all done it at some point, no matter how ‘innocent’ and ‘harmless’ it might have come across as. We blamed the victim. We shouldn’t have; but, we did.

While it might seem quite inconsequential when it comes to falling off the edge, it gets problematic when we apply this tactic to more complex issues, like assault.

And this isn’t just India; it’s America, it’s Europe… Look at your news feed. It’s global. But, most of all it’s wrong.

Then, why do we – society, as a whole – continue to do it?

The answers apparently lie in deep-seated psychology as we’ve been given to understand.

According to Sherry Hamby, professor of psychology at the University of the South, and founding editor of APA’s Psychology of Violence journal, the biggest factor that promotes victim blaming has to do with the ‘Just World’ Theory.

“It’s this idea that people deserve what happens to them. There’s just a really strong need to believe that we all deserve our outcomes and consequences,” she explains in an interview with The Atlantic.

In Psychology Today, Ronnie Janoff-Bulman, Psychologist, University of Massachusetts, reasons that we believe in our personal invulnerability because of our ‘positive assumptive worldview.’

As human beings, we live in a bubble, believing that good things happen to good people and bad things to bad ones. The down side to it is when we justify our wrongful deeds under the guise of righteousness; we continue to believe that we are good. And so, we deserve good. And to those whom bad things have happened, well, they deserved it.

In theory, it seems relatively harmless a concept. But, in practice, it ostracises a victim. We, as a society, are telling someone they deserved to be harmed. They ‘asked for it’. And we believe it. Case in point: Almost every politician’s statement post a rape/assault case, almost every lesser knowing person in society and the perpetrators.

“In my experience, having worked with a lot of victims and people around them, people blame victims so that they can continue to feel safe themselves,” explains Barbara Gilin, professor of social work at Widener University. “I think it helps them feel like bad things will never happen to them. They can continue to feel safe. Surely, there was some reason that the neighbor’s child was assaulted, and that will never happen to their child because that other parent must have been doing something wrong.”

Picture this:

A woman wearing a short skirt in a crowded metro gets groped and assaulted in the general compartment by a serial offender who’s had a record of leching, eve-teasing and molesting women. Who is to blame? How you answer this question is proof of how you perceive reality. And more often than not, it’s flawed.

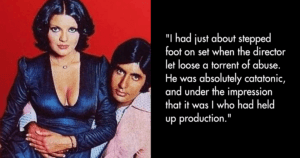

There’s another side to the story: How we’re conditioned to sympathise with the perpetrators who are, almost always, powerful individuals.

In a Vox interview, Cornell philosopher Kate Manne dubs it as ‘himpathy’, the disproportionate sympathy powerful men reap over their less powerful female victims, she says.

“It’s as though her perspective, her story, her experience, doesn’t exist in his mind. It’s a refusal to take the female perspective seriously, and it amounts to a willful denial rather than a mere ignorance.”

“The fact that the male perspective is primary in our culture causes a lot of hostility toward women who come forward and testify against them in these cases, offering a challenge to their otherwise good names or hitherto good reputations, which is of course what breaking silence involves”, she goes on to explain.

We never blame the perpetrator for having taken advantage of a woman under the influence of alcohol, or wearing a short skirt, or walking down a street alone at night. We blame the woman. Why did she have to drink, wear that skirt or get out at night? We still live in a bubbled idea that the victim had a choice and the perpetrator didn’t. What were they to do, after all?

‘Ek ladki khulli tijori ki tarah hoti hai‘ is a line that should be inked into the skin of every person who blames the victim because, they truly believe she deserved it. By which decree, if we lock our car doors, carry pepper spray, don’t eye men, cover our selves completely, and don’t go out partying, we should not be sexual assaulted. But, that’s hardly the case.

Victim blaming is never right. Sure, there will always be the instance of innocent, until proven guilty – a benefit of doubt we readily offer to the perpetrator. But, before pronouncing our own personal judgments, can we take a moment to stop and consider this:

– A victim speaking up about assault and reliving the incident, along with the trauma of being shunned and ostracised.

Now, ask yourself one question: