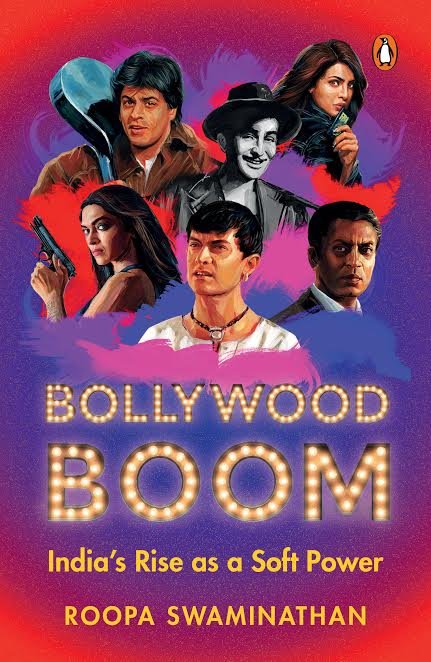

The following is an excerpt from Bollywood Boom by National Award–winner Roopa Swaminathan in which she explores how Bollywood films have re-entered Pakistan despite being blocked for decades.

“The Telegraph, in its article titled ‘Bollywood Is Killing Our Industry, Say Pakistani Actors’, says that Lahore’s Lollywood is the equivalent of Bollywood in Pakistan. During its heydays, the 1960s, Lahore produced hundreds of Pakistani films locally. But with the advent of the VCR, piracy and illegal smuggling of Bollywood films became the norm and much of Pakistan’s single-standing cinema houses closed down, either to become parking garages or shopping malls.

As the era of globalization began in the 1990s and the Indian economy became more and more vibrant, the situation in Pakistan veered in the opposite direction. Still caught up in its conservative Islamist identity, Pakistan found its economy in the doldrums and the domestic film industry from Lahore almost died out. The extravagant-looking Bollywood spectacles that were available in the black market did not help, and it became the go-to form of filmi entertainment for the average Pakistani.

By 2005, Lahore had produced barely twenty films a year, and in 2010 it produced a mere nine films. Unfortunately for Lahore, Bollywood films were turning out to be big hits. Karan Johar’s definitive look at the plight of people with a Muslim last name, My Name Is Khan (2010), opened to packed houses in Pakistan. British journalists reportedly saw Pakistani audiences clapping their hands when Shah Rukh Khan says in the movie, ‘My name is Khan and I’m not a terrorist.’

Interestingly enough, Islamization or narrow nationalism was the reason the state leadership banned Bollywood films from 1960s through 2005. But by 2012, the economics of Bollywood in Pakistan had changed the situation dramatically. Despite the wobbly relationship between India and Pakistan at that time, the Pakistani government realized that imposing an entertainment tax on theatre tickets would result in a solid income for the state; basically, they had too much to gain economically to revert to banning Indian films.

The Pakistani film industry has seen a bit of resurgence since 2013. But when a popular Pakistani entertainment website, HipinPakistan (HIP), conducted a survey among a cross section of top Pakistani film artistes in November 2016, the results were very interesting. HIP found that while the Pakistani film industry was clearly on the rise, it was still nowhere close to being able to sustain itself.

According to HIP, Pakistan now has around ninety film screens and makes less than fifteen films a year. If these minuscule number of theatre screens are to remain open, Lollywood has no other option in the foreseeable future than to import foreign cinema. And given the language and cultural commonalities between the two countries, Bollywood remains its cinema of choice.

However, since the Ae Dil Hai Mushkil controversy erupted in October 2016, it has been uncertain how things will play out. When many distributors in India refused to release the film because it starred Fawad Khan and also warned that future Bollywood films starring Pakistani actors will meet a similar fate, Pakistan retaliated by banning Indian films.

HIP spoke to a cross section of Pakistan’s film elite and found that the film industry did not support this political move by the government. From Pakistani actors to writers to directors to producers and distributors, almost all of them were against it. Like director Ahsan Rahim said, ‘Indian movies brought people to the cinema, so banning them would affect the business.’

Almost as proof, the headline of a lead story in HIP, published on 12 December 2016, read, ‘Pakistan Cinemas Struggle to Survive’. The article reported a 60 per cent decline in footfall in Pakistani theatres since the Bollywood ban took place a few months back. The article painted dire straits for the local industry: newer movie halls being put on hold, Pakistani producers pulling money from their own industry since their existing movie halls were running empty, and employees working in the cineplexes being laid off.

Eventually, Pakistan announced its decision to roll back the ban on 18 December 2016. It is clear that the relationship between India’s film industry and Pakistan’s film industry is asymmetric, just as the one between their respective economies, with Bollywood and India being far less dependent on Pakistan than vice versa.

Also, for the crème de la crème artistes of Pakistan—be it singers, actors, writers or directors—crossing over to India and becoming a part of the much larger and more vibrant Bollywood industry remains their biggest goal. After relations between the two states thawed in the new millennium, the Indian government made it easy for Pakistani artistes to get visas to come and work for prolonged periods of time in its country.

From Fawad Khan (Kapoor and Sons, Ae Dil Hai Mushkil) to Imran Abbas (Creature, Jaanisaar) to Ali Zafar (Mere Bhai Ki Dulhan, Dear Zindagi) to Mahira Khan (Raees) to the enormously popular Pakistani band Junoon, all of them made their way to Mumbai seeking fame and fortune on a larger scale. However, at the time of writing this book, the future of Pakistani artistes in India hangs in balance.

But the argument within Pakistan over Bollywood rages on.”

You can buy Bollywood Boom published by Penguin Random House here.

Feature Image Source: Reuters (File)