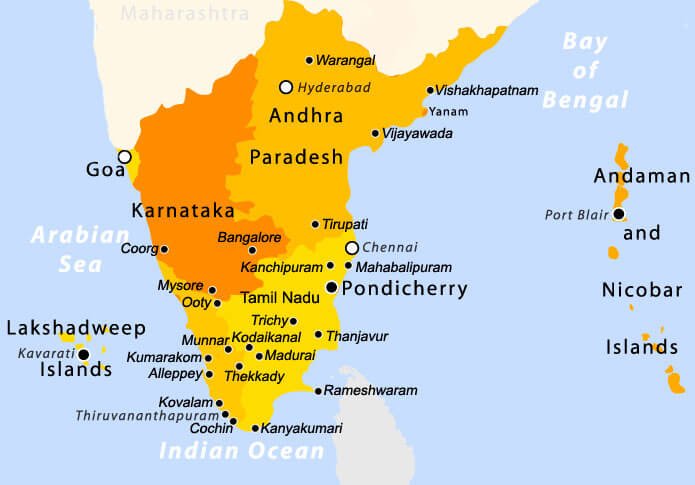

The Cauvery water sharing dispute reached massive proportions with police firing claiming one life in Bengaluru yesterday evening. Protesters took to the roads of Bengaluru chanting ‘We will give blood but not Cauvery’. Earlier this month, the Supreme Court ordered Karnataka to release 15000 cusecs of water daily to Tamil Nadu for 10 days. Since then, there has been large-scale vandalism in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, with the the deployment of 15,000 police personnel in Bengaluru. Prohibitory orders under Section 144 were imposed in Bengaluru and Mysuru, areas around four reservoirs in the Cauvery basin, and Pandavapura in Mandya district.

However, the issue of sharing the water of the Cauvery river is not a new one. In fact, the dispute dates back to the British era, and has, over the years, undergone several changes.

ScoopWhoop News spoke to Kshithij Urs, professor of Public Policy at National Law School of India, and the Convenor of the People’s Right to Water Campaign to understand the core issue better.

The first agreement on the sharing Cauvery river water dates back to 1892, between Madras Presidency and the princely state of Mysore. How did the Imperial government deal with the issue then?

The princely state in Mysore was not under the British rule. The Madras Presidency constituted of parts of Kerala (Malabar Coast) as well as Karnataka (South Canara/Dakshin Kannada) It was unfair to begin with, and negotiations were extremely difficult. The pact was signed between Chamaraja Wadiyar, the then ruler of Mysore and the British administration. Mysore needed water for irrigation projects, but was met with British resistance. It was then that a conference was held and the agreement was finally signed in 1892. But according the agreement, water was not just to be used for irrigation but also for providing hydroelectricity to the Kolar gold mines in Karnataka, that were then under the British. So a lot of factors affected negotiations between Captain Daws and the Raja of Mysore, but for Mysore it was mostly a win-win situation.

What changed after Independence in 1947 and the subsequent reorganisation of the states in 1956?

After reorganisation, Tamil Nadu and Pudduchery fell in the East Coast while states like Dakshin Kannada, Kerala and Coorg went to the West Coast. The immediate problem after 1947 was the increase in stakeholders and the ambiguity in the existing water laws. The Interstate River Water Disputes Act, 1956 does not have clear terms or proper distress management mechanisms (water sharing in times of crisis such as droughts).

Riparian right is a natural right, which means any riverside dweller, or anyone who lives beside a river or water body can access or use the water, in other words, has a natural right to do so in lieu of his position. After the reorganisation of states, state boundaries took away these natural rights from riverside dwellers.

The increase in stakeholders is evident by the internal disputes among various districts within states. Within Tamil Nadu, three distinct groups fight over the sharing of the water. In Karnataka, west flowing rivers are being planned to be rerouted to the East Karnataka. Boundaries create problems for people to practice their riparian rights.

Why is water such an intrinsic issue between the southern states?

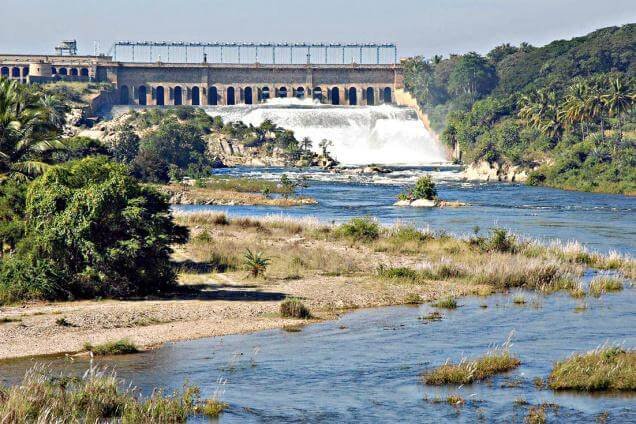

It is not just water sharing, it is water of Cauvery river that is the issue. Karnataka has many rivers but Tamil Nadu does not. Only a few rivers originate from Tamil Nadu, and east-flowing Cauvery, one of the biggest rivers in the region, originates in Kodagu in Karnataka, passes through major tracts of Tamil Nadu. But in river-fed areas, there are always disparities between people living upstream and those living downstream. Take the Mandya region in Karnataka for example. After the construction of the dam, Mandya became highly irrigated and farmers there began growing cash crops like paddy and sugarcane. So it’s not just water. Agriculture and economy is also tied to it.

Are their deeper socio-cultural factors that make water sharing such a heavy political issue?

Throughout the world, civilisations have been built on rivers. The evolution of Indian civilisations have been more complicated due to the country’s linguistic and cultural variety. This is important to understand since it is just an oversimplification to say that this issue is a Kannada vs Tamil issue. The demographic make-up of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu is very different. In Karnataka itself, in the Western Ghats, Coorg, is inhabited by pre-Dravidian tribals, the erstwhile Kodagu district in Karnataka, where Cauvery originates, there has even been a fair bit of French mixing due to the introduction of Coffee plantations by the British, resulting in the landed communities of Coorgis, some of whom claim French descent. In Mandya, the Gowdas are the dominant landed community. In fact there is also a rudimentary separatist movement within the state. All these communities feel a natural right on Cauvery. Tamil Nadu on the other hand is very different. The Tamil movement of assertion was one of self respect, where they looked to the entire society for reform. The KAnnada assertion feels more like all sound and no content.

Why has the issue become such a heated one now?

Well, several factors are to be blamed for that. Firstly, increasing global warming has caused massive climate shifts. There were no rains in the catchment areas of Cauvery this year, something which is usually taken for granted.

Secondly, people in Karnataka feel snubbed by Delhi, and to some extent, it’s for valid reasons. Tamils on the other hand, are sanskritized and are too assimilated into the dominant cultural paradigms. These factors are often used by politicians to play off parties against one another. No real effort is being made to actually save water. States blame each other for the massive deforestation, yet another cause for reduction in rainfall. Excessive politcization of the issue has been a problem.

The main issue here is that nobody is thinking of saving water. Neither Karnataka, nor Tamil Nadu is practicing rainwater harvesting, which could easily solve a large part of the problem.

Feature Image Source: Youtube