As soon as the news of yet another Sunni-Shia riot broke out in Lucknow, Mukesh Verma rushed to the spot with his camera. For the uninitiated, Lucknow witnesses more riots between the two communities than any other Indian city and, every time it happens, it’s violent.

Verma followed the mobs running amok, brandishing stones and burning with rage, but tried to remain in close vicinity to the police.

Till he found himself lost in a narrow lane with no cop in sight and at a stone’s throw away from the rioters.

Verma was petrified. He was ready to trash the camera if the rioters so wanted and prayed that’s all they’d ask. But he had covered too many such riots to be hopeful.

Just then, a familiar face in the crowd identified him and called out to the mob to spare the poor reporter. Surprisingly, the mob turned away and went in a different direction to vent out their fury.

Verma, a print and broadcast journalist based in Uttar Pradesh’s capital city, can recall many such moments from his 15 years of journalistic career. “Such is the life of a field reporter. We rush to spots everyone is running away from.”

A hardened reporter, Verma knows his job is fraught with danger. And he knows there is no one to turn to. Neither the cops, nor the owners of the media channels and publications he freelances for.

But when he learnt yesterday through news portals that a Mumbai-based senior executive of a giant media house, Arnab Goswami, is getting 20 guards to protect him round-the-clock, Verma is more than irked. Even disheartened.

Verma explains why. “Whenever we field reporters express concerns about the dangerous nature of our work, we are told it’s our choice. How it was entirely our decision to take up this thankless job. But it’s ironic that while our protection is no one’s responsibility, the security of a star news anchor ranting from an AC room is government’s concern.”

Like Verma, reporters in India, especially those operating in small towns and away from metros, are at perpetual risk. Reporters know it and figures don’t lie. In 2013, India emerged as the second most dangerous place for journalists in the world, second only to war-town Syria, and has more or less held the dubious slot since.

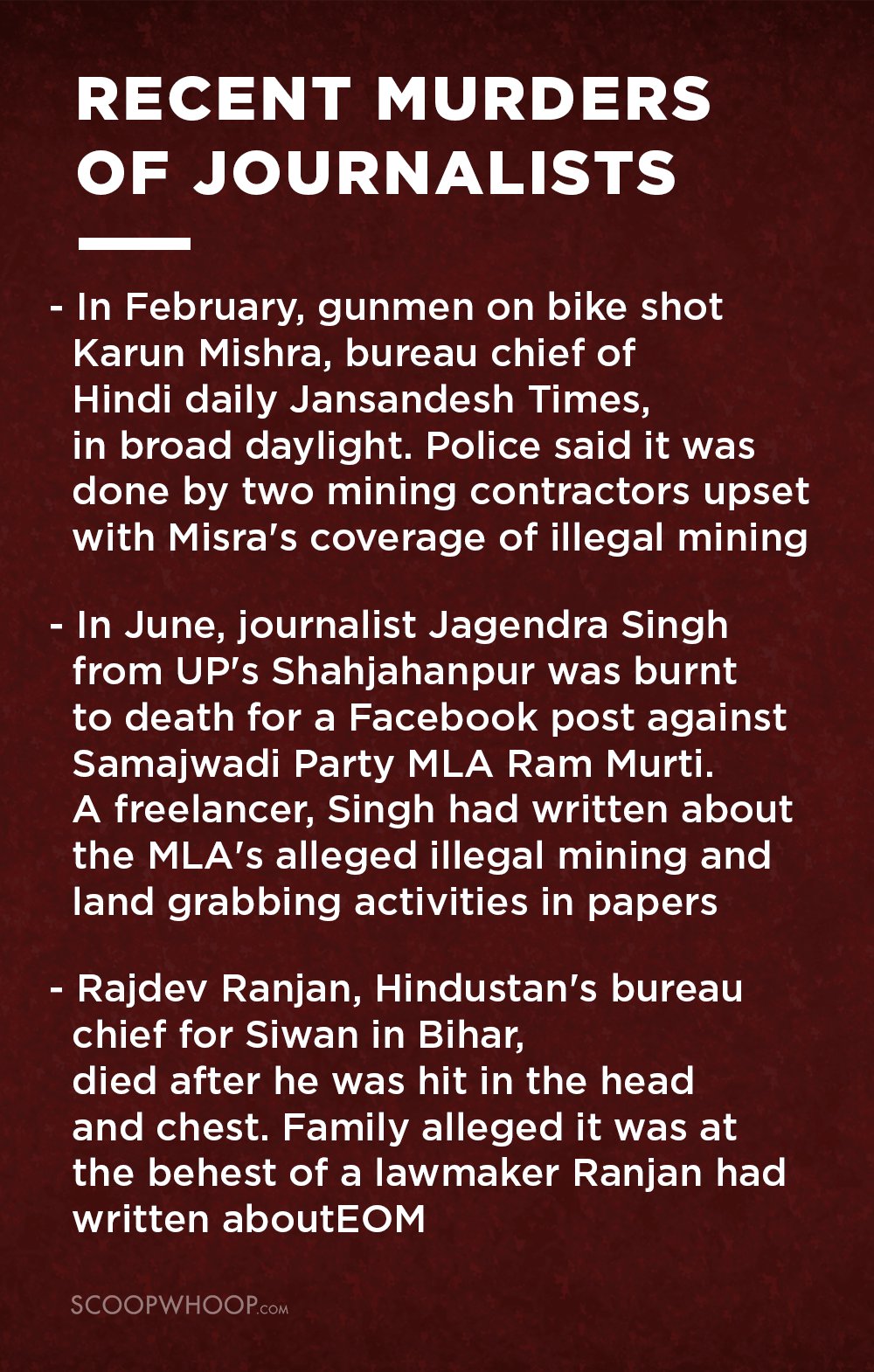

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, 40 journalists have been murdered in India since 1992, 22 of them with a confirmed motive.

In 2015, when only Syria and Iraq lost more journalists than India, the media watchdog ‘Reporters Without Border’ explicitly said that journalists in India “daring to cover organised crime and its links with politicians” are exposed to violence.

Verma has lived this reality. He has ventured into the no-go areas during communal clashes, found himself stranded in the middle of an isolated village at midnight while on the way to covering a police raid, and been hauled up by goons. Luckily, he was let off with a warning.

Polls in sight, his workplace Lucknow is a simmering communal cauldron these days. Verma uses his experience to evade risk and that’s all he can bank on anyway. “In all these years, there is not as much as a helpline for journalists, let alone a system that ensures we are safe while are on duty.”

Verma is experienced enough to know that no one is accountable for his safety, not even his bosses. “We asked for the risks when we became journalists. That’s the attitude,” he says.

And here, Verma points out yet another irony in the government’s move to provide Goswami Y-category security. “Anchors and top media executives have a free run in the TV studio while the ground reporter faces the heat. It’s really the reporters who are exposed to risk while their bosses are breathing fire in the safe havens of their offices.”

Verma recalls a recent incident to elaborate. He had spent an entire morning chasing a politician for an interview and eventually managed to catch him. “But his supporters heckled me. They abused me after learning what channel I was reporting for. I soon got to know that an anchor in the Delhi studio had been mocking the neta all morning.”

“How on earth would I know what was airing?” he said, exasperated. “I barely escaped being beaten up.”

Verma has been witness to enough incidents to understand that for all the dangers they involve themselves in, they are paid a pittance and enjoy no job security. Just last month, a fellow reporter and Verma’s friend was forced to resign after his story exposed corruption by a local politician. “The channel authorities wanted him to apologise to the politician but my friend refused to. He was asked to leave.”

And this leaves him more disturbed about Goswami’s privilege. “I heard he earns crores for the job, He can certainly manage his own private security,” says Verma.