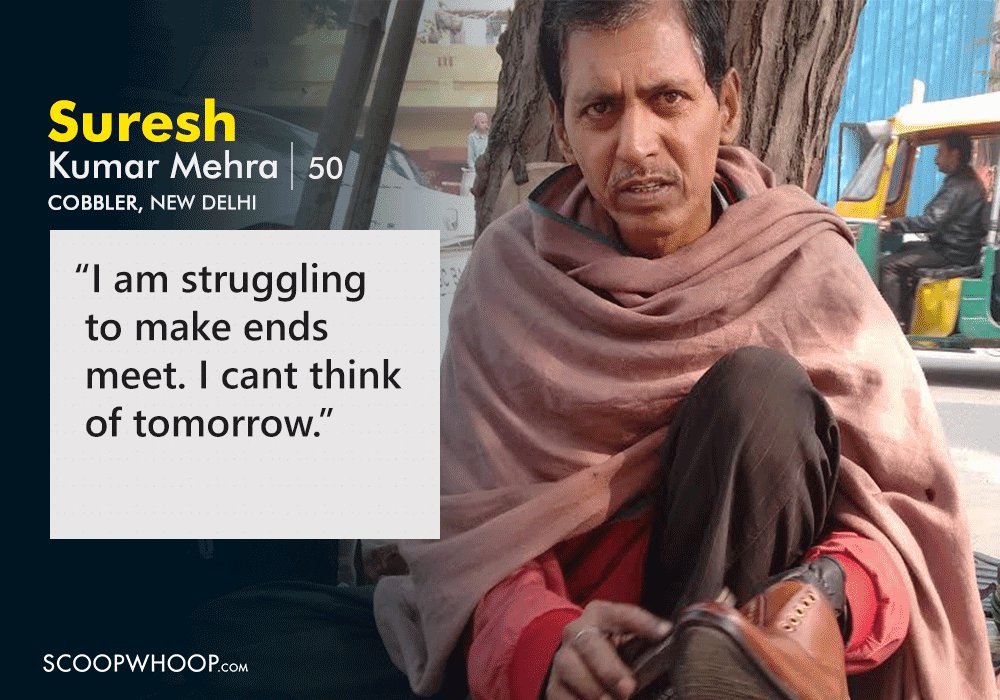

There is an ATM not far from Suresh Kumar Mehra’s shack at the entrance of CR Park Market-2 in south Delhi. The queue leading to it coils around Mehra’s cobbler stall. Mehra calls it the “death noose”.

“It seems like I am choking,” laughs Mehra, making a choking gesture with his hands.

“Arre! Dekh ke chaliye na bhaiya! (Look where are you walking!),” says Mehra, as a flurry of feet almost topple his carefully stacked shoe rack in a rush to fill a gap in the queue.

Forty-years-ago, Mehra’s father shifted from Alwar in Rajasthan to Delhi in search of a better life and set up shop at the very spot.

“Thank god he is dead, it would have pained him to see us scraping the bottom like this,” says Mehra.

It has been a tough month for Mehra and his family. That fateful night when Narendra Modi addressed the nation, declaring the ban on Rs 500 and Rs 1000 notes, life took a definitive turn for them.

“The first week was particularly difficult. I didn’t earn anything for almost three, four days,” he says.

And since Mehra is a daily-wage earner, his family had to make do with the bare minimum.

“We only had Rs 300 with us then and a week’s ration. At any given point of time, we do not have more than Rs 500 with me,” says Mehra.

Mehra has two sons, one studying in college, another in school.

“Their education is anyway financed by their maternal uncle who works in the Gulf. He comes down once every year and pays their yearly fees. Had it not been for him, I would have had to pull my son out of school,” says Mehra.

Mehra, who earns around Rs 8000 a month on average, says he earned Rs 3000 last month.

“The bulk of that was done in the first eight days of the month,” he says.

Did his business pick up after the initial shock wavered off?

“Hardly. People do not have ready cash with them now. They are avoiding cash transactions unless it’s absolutely necessary. Getting ones’ shoes fixed or polished is not really a necessity,” says Mehra.

Has Mehra considered switching to cashless transactions?

“It doesn’t make much sense to me. I don’t have a smart phone. I cant afford one. I don’t even have a bank account. Moreover, I am scared of all these new technologies,” he says.

However, he plans to open a bank account at the Jan Dhan scheme.

“When I went to our local bank to open an account last month, I was asked to come back after the frenzy dies down. I don’t feel like going now because I am too busy making ends meet. And what will I open the account with? I have barely Rs 200 with me now,” says Mehra.

Does he see something good coming out of demonetisation?

“People tell me in the long run, it will be good for the country. But I am too busy struggling with my immediate problems to think about the future,” says Mehra.

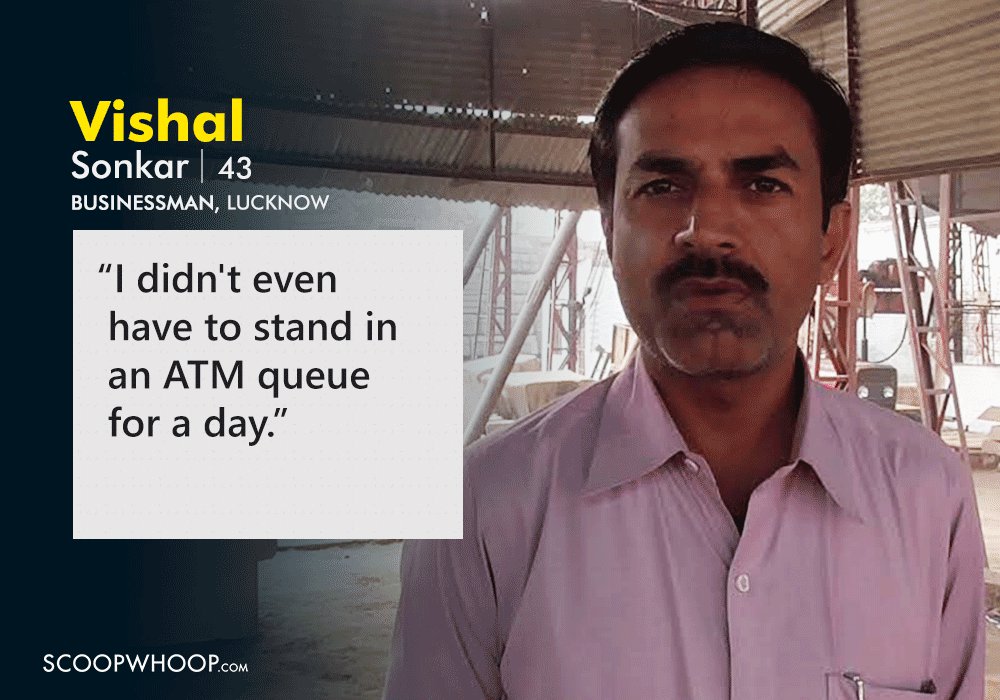

How does one survive without a single Rs 100 note for a whole month? Ask Vishal Sonkar, 43, a businessman from Lucknow, who had just Rs 5000 with him in the banned Rs 500 notes when Modi announced demonetisation exactly a month ago.

“I used most of the Rs 500 notes to buy petrol for my two cars. I deposited the rest in my bank account,” says Sonkar, who runs a travel agency at the Hazratganj area of Lucknow.

Did he not face problems getting his customers to pay through card? “Most of our payments are made through online transactions anyway. Post the demonetisation announcement, our customers were actually relieved about the fact that we accept cards,” says Sonkar.

Yet, Sonkar feels, that there has been a definitive slump in the market. “Business has gone down by at least 30 per cent for me,” he says.

What about paying salaries to his employees? “I pay my employees through cheques,” says Sonkar.

Sonkar, who lives with his wife and a school-going daughter, uses cards for most of his domestic transactions.

Did have problems paying his domestic help and security guards? “They do have bank accounts but they were apprehensive about online transactions. I explained the process to them and transferred money into their account. I paid them Rs 100 extra each as a compensation,” says Sonkar.

However, Sonkar does realise that he has transferred the burden of standing in queues to other people. “I didn’t have to stand in ATM queues even for a day. I do realise that I am amongstthe privileged few,” he says.

Does he think that India is prepared to be a cashless economy yet. “I do feel that a lot of people will benefit for this. There will be a lot of transparency too. But what about the unorganised sector?” he asks.