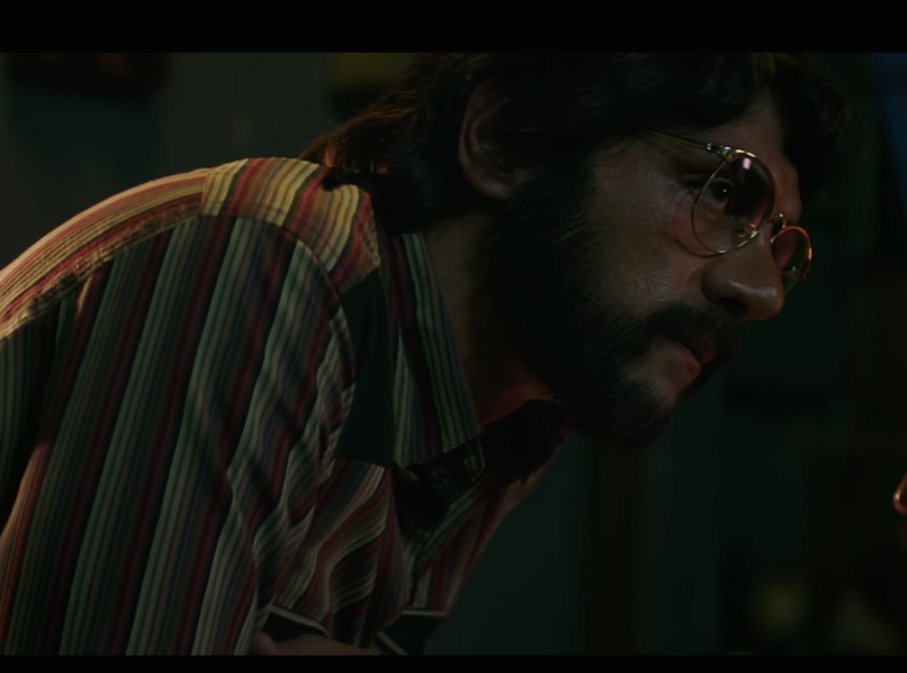

Since it’s the star of the enterprise, I thought it would be only fair to begin this review with a detailed description of Rampal’s prosthetic nose in Daddy. As far as prosthetic noses go, this one is the cream of the lot.

It’s bulbous but it doesn’t lack symmetry. A nose-bridge, as straight as Baba Ramdev’s back, runs through the middle of it. I am tempted to call it hook-shaped but it’s not curved enough for that term. I wish I could figure out if there are stray strands of hair sprouting from it, but director Ashim Ahluwalia ensures that there is a certain amount of mystery attached to it.

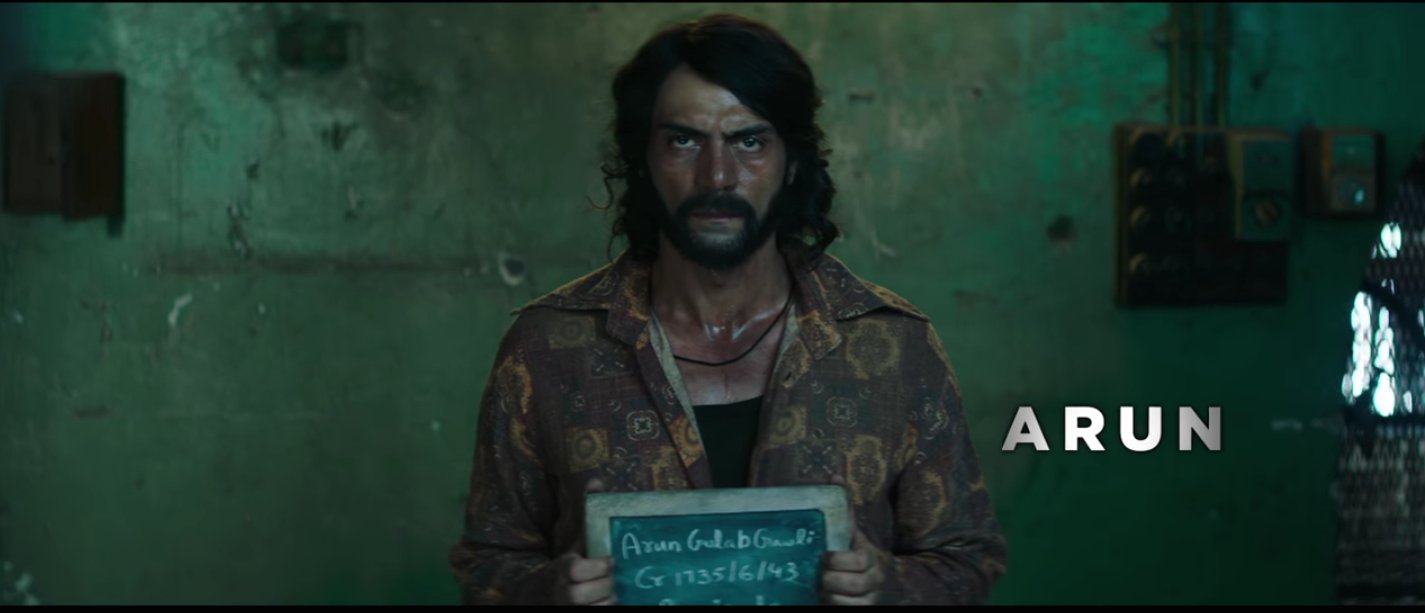

Make no mistake, the nose in Daddy sits bang in the middle of Arjun Rampal’s much-eulogised, chiselled face not only for cosmetic purposes. It’s a multi-functional device. It helps Rampal get into the skin of the character – his hook-shaped nose was the most distinctive feature of gangster-turned-MLA Arun Gawli’s face.

It also acts as a shield between the audience and Rampal. A man who has spent close to two decades trying to shrug off the wooden-actor tag. In the film’s most crucial moments, Rampal’s face is hidden under the shadow of the nose. The background music, lighting and urgency of the camera movements tell us that the scene is reaching its emotional climax. As an audience, you can only hope that behind the dizzying heights of the nosebridge and the deep ravines of the cheekbones, there is some acting happening.

It’s not for nothing that I will proceed to say that Daddy is nose in search of a film.

After the breathtakingly beautiful Miss Lovely, where with the aid of an almost stoic Nawazuddin Siddiqui, Ahluwalia explored the innards of B-grade Bollywood film industry, Daddy comes across as a half-hearted artistic compromise.

Yes, Ahluwalia retains his eye for details. The period detailing in Daddy is almost obsessively authentic – a popular number from the Govinda-Neelam starrer, Love 86 (1986) plays in the radio during a sequence set in 1986, the mid-1980s dhoti pants and sequin tops are duly acknowledged too. His cinematographer ensures that we can almost breathe in the sooty air of Mumbai’s industrial chawls of the 1980s.

Even as he tries to make us buy into the legend of Arun Gawli, son of a jobless mill worker who is propelled to a life of crime, he never manages to connect with the audience. Every attempt to humanise the startlingly robotic Rampal with an emotional scene is sabotaged by the nose.

Eventually, his journey to gangsterdom becomes almost pornographic in its unfolding. One clinically constructed set piece after another.

There is, of course, an almost comical cameo by Farhan Akhtar, who plays a character inspired by Dawood Ibrahim. Armed with an Elvis Presley wig and an assortment of sunglasses, Akhtar spends most of his screen time scooping out firni from glass tumblers. On the rare occasion that he is shown moving in front of the camera, he is all laboured swagger.

I have a sneaking suspicion that best buddies Rampal and Akhtar are living out their 1980s fashion fantasies here, but for Ahluwalia’s sake, I hope it isn’t true.