They’re young, on holiday, drunk and sometimes high, and they decide to jump from their hotel or apartment balcony into the pool. But some miss and end up in hospital… or worse, dead.

The so-called “balconing” craze has taken off to such an extent in Spain’s Balearic Islands that doctors at the Son Espases hospital in Palma de Majorca — a major trauma centre — decided to study the phenomenon.

“It’s endemic,” says Xavier Gonzalez, head of surgery at the hospital who participated in the study.

“It seems that… it’s like an initiation rite for some tourists, whose parents already came here when they were young.”

The 2010-2015 study only covers patients who were treated in hospital and not those who died while “balconing” — a term that refers to people who throw themselves into pools or fall while trying to get to another balcony or simply leaning over.

Altogether, the hospital treated 46 patients during that time, more than 60 percent of whom were British, followed by Germans and then Spaniards, the study found.

Only one woman was involved, all the others were men, aged 24 on average. The fall itself was from an average height of eight metres (26 feet).

Alcohol was involved almost every time, and in close to 40 percent of the cases, drugs also played a role.

Altogether, the craze has cost 1.5 million euros ($1.7 million) in hospital fees, Gonzalez says, as patients can remain in intensive care for a long time, some ending up paraplegic. It is unclear exactly how many people have died from “balconing”, but Spanish media have reported more than a dozen deaths over the past five years.

The craze also happens on Spain’s northeastern Costa Brava, but it is most prevalent in the Balearic archipelago, which includes Magaluf and Ibiza among its famous resorts, Gonzalez says.

Further afield, Bulgaria has also been hit by “balconing.”

In a bid to curb the trend, authorities in the Balearic Islands have implemented measures — printing preventative leaflets and handing out fines to people caught trying to jump from balconies.

“As a precaution, when they see a group of young people arrive, hoteliers no longer put them on top floors but on the ground floor,” adds Gonzalez.

Britain has also tried to warn its nationals of the dangers of throwing themselves off balconies.

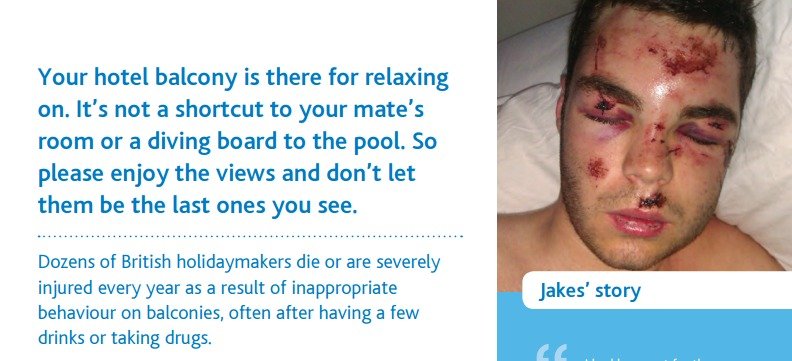

In 2012, the British foreign ministry published leaflets called “Booze and Balconies Don’t Mix,” using the story of Jake Evans from Liverpool.

Drunk, he fell from the seventh floor of his flat in Magaluf in 2011.

“I hit every balcony on the way down, as they jutted out like steps,” he was quoted as saying.

“I landed on a sun lounger which broke my fall and probably saved my life.

“I fractured my skull, broke front teeth which pierced through my upper lip, snapped my right wrist and broke all the fingers on my right hand,” he said.

“The accident has changed my life… I have recurring problems with my back and right wrist and doctors have told me I probably always will.”