This Friday’s big release is Nitesh Tiwari’s Dangal . For Aamir Khan fans this is the motion picture event of the year. But even if you are not an Aamir-phile, you cannot deny that the trailer of Dangal looks promising.

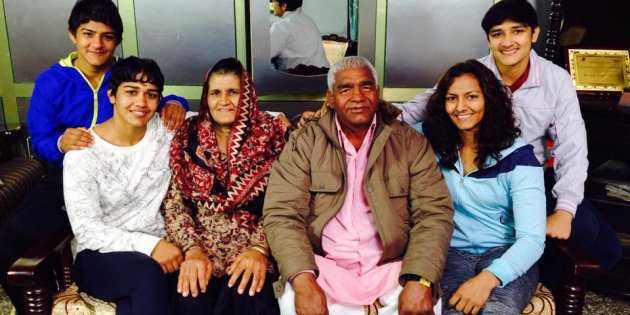

Unless you have been living under a rock for the past few years, you know that film is that it’s based on the life of Mahavir Singh Phogat, who is an Indian amateur wrestler and senior Olympics coach. Phogat was awarded the Dronacharya Award by the Government of India. But was he really the tyrant that the song haanikarak bapu makes him out to be?

Here is an excerpt from the authorised biography of Mahavir Singh Phogat which tells you how Geeta Phogat, who won India’s first ever gold medal in wrestling at the Commonwealth Games 2010, was trained by Mahavir Phogat.

Mahavir couldn’t become an international wrestler himself, but he knew he would live to fight another day. He believed hardship only made a person stronger. When it came to training the children, he stuck to this basic formula: Train as hard as you can.

Geeta, the eldest of the lot, was 12, while Ritu and Vinesh were just six when they, along with their cousins, were introduced to wrestling in October 2000. Over a decade later, the trainees fail to remember when they grew up enough to travel alone across the world.

It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that through their formative years all the girls did was spend time in the akhada. The cycle of wrestle-eat-sleep-repeat seemed never-ending at the time.

‘The first few days were fun for us. Being the youngest among all the children, Vinesh and I were let off easy,’ recalls Ritu, the third of Mahavir’s four daughters. ‘We would sit and chuckle at the sight of our elder cousins sweating it out. But the fun days didn’t last long. A week into the training, Papa pulled us into the rigorous schedule, too. It no longer mattered who was six and who was 12.’

‘I remember how we would always look for an opportunity to skip training. Sleeping for even 10 extra minutes in the morning would be a luxury for us,’ she adds.

If, initially, Mahavir’s decision to train the girls in wrestling had made him a subject of mockery among the villagers, later it was his brutally hard training regimen that became the talking point among the locals.

‘As a kid, I had a lean body. So when my mother saw me undergoing the demanding training or getting a bashing from Tauji, she would be reduced to tears. But she could only shed tears, for no one except our grandfather had the nerve to intervene in the training or say anything to Tauji,’ says Rahul.

This is not to say that Mahavir’s father, the former wrestler, did not intercede.

‘Our grandfather had to step in a couple of times to stop Tauji from hitting Geeta or Babita. Once, Geeta was unable to follow Tauji’s command and repeated an error. His frustration got the better of him and he began hitting her with a stick. Our grandfather, who was standing nearby, saw this and immediately entered the akhada. We all watched, stunned, as he grabbed Tauji by his neck and warned him that if he hit the girls again, he’d have to face severe consequences. While Tauji let Geeta off then, his message to all of us was clear: No errors would be tolerated,’ Rahul adds.

‘While other children of our age would sleep cozily in their beds, we were expected to be at the pit for training even before the cock crowed. This remains unchanged, as even today whenever we [Geeta, Babita] and the other sisters are home, we have to follow the same routine. Back then, if any of us ever fell short of Papa’s expectations during training, he would severely reprimand us. We would often be bawling and making a spectacle of ourselves in front of villagers, who would wake up hearing our cries at dawn. The villagers started calling him a “devil” for making us cry so often. But they all knew his temper, so they considered it best to leave the matter to him,’ says Geeta.

But Mahavir was not always the disciplinarian that he was in the pit. His family knew him as a cheerful person, who loved spending time and playing with the children. But as he stepped into the role of a coach, he became a man of few words and big goals. This trickled down to his trainees who, along with other family members, noticed this huge transformation in his personality.

‘Papa became a completely different person as a coach. Earlier, he loved spending time and playing with us. Since his wrestling days, he was in the habit of exercising in the morning and he would often take us along, challenging us to race him. His strong, bulky body would never fail him in sprints, leaving us far behind. Back at home, he would talk to us and play pranks on us. But all this stopped when he took to coaching. His jokes and pranks were replaced by commands and reprimands,’ says Geeta.

Mahavir acquiesces.

‘As I stepped into the shoes of a coach, the role came with the responsibility of maintaining a strict demeanour at all times. Hence, the jokes took a back seat and discipline became a priority. I was no longer just a father or an uncle, after all. As a coach, I had to make sure they were disciplined both on and off the field. A sportsperson’s routine throughout the day reflects his or her attitude towards training. As all of them were quite young when we began, they could not comprehend the effect an undisciplined lifestyle would have on their future performance.’

Paying no heed to anyone’s opinion of him as a coach, Mahavir was willing to go to great lengths to ensure that the children got the best training. With Olympic glory constantly on his mind, he understood a wrestler’s need to acquire a blend of strength, speed, endurance, skill and mental resilience.

•

When Mahavir made up his mind to coach his family’s children in wrestling, he began by making an akhada right in the centre of his courtyard.

‘The akhada is a pious place for wrestlers. As such, if placed within a house, it is set up away from the living area to keep the wrestlers away from domestic chores and provide tranquillity to train without any distractions. One is not supposed to walk through it with or without shoes. However, due to space constraints, we had no option but to build the akhada in the middle of our courtyard. Every time we entered the house or left it, we had to walk through it,’ says Geeta.

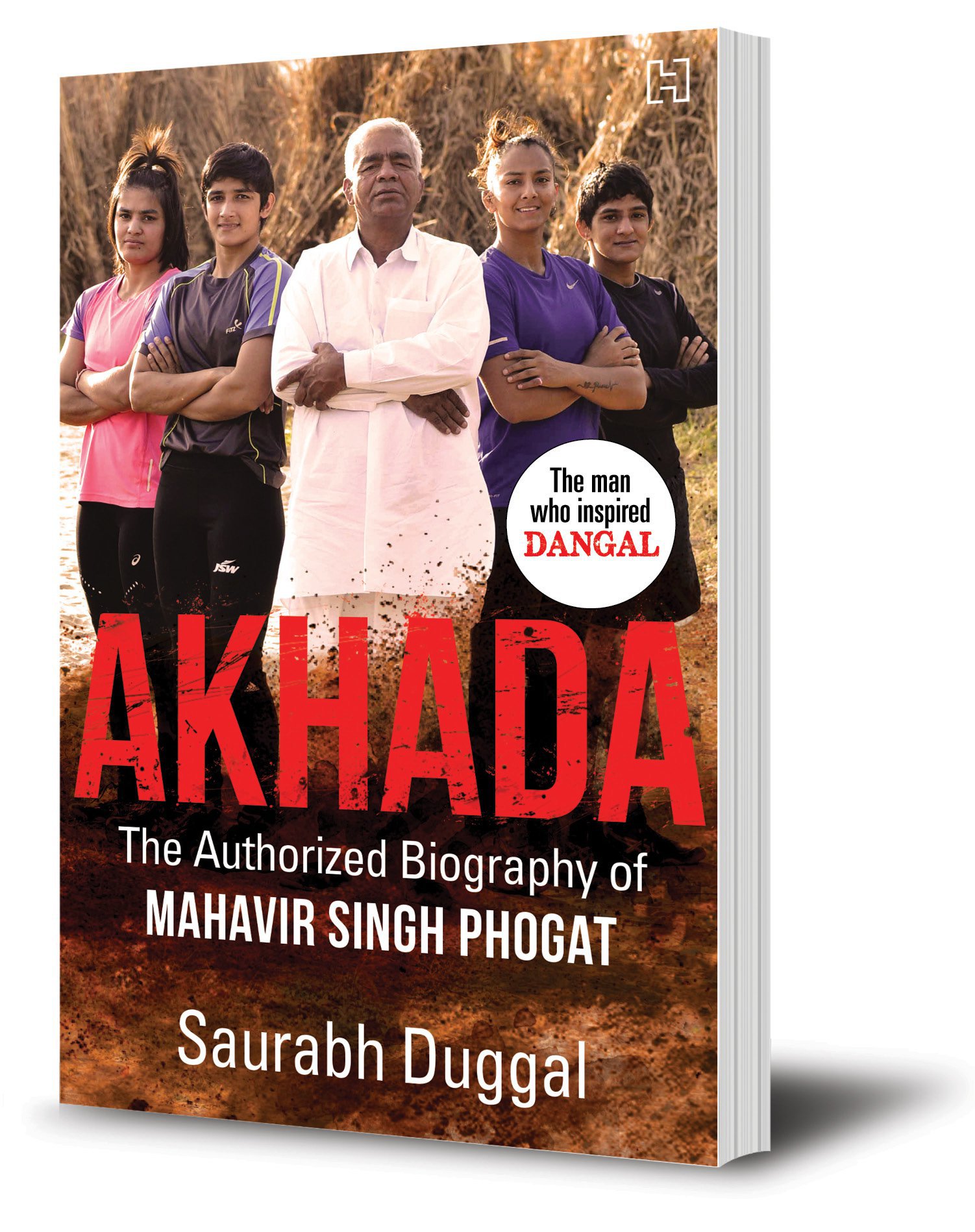

Excerpted with permission from Akhada: The Authorized Biography of Mahavir Singh Phogat by Saurabh Duggal, published by Hachette India.