There is a point in Shree Narayan Singh’s Toilet Ek Prem Katha where the agenda of the enterprise bobs to the surface, like unflushed poop in a commode. We all knew which side of this toast is buttered. But really. Did we need to have characters singing praises of “notebandi” to hammer things in?

This film could easily have been so much more had the filmmakers chosen to exercise some restraint. After all, it addresses one of the biggest problems that plagues our country: defecation in the open. But the suffocating level of ass-licking on display kneecaps any legitimate chance the film had at embracing social satire.

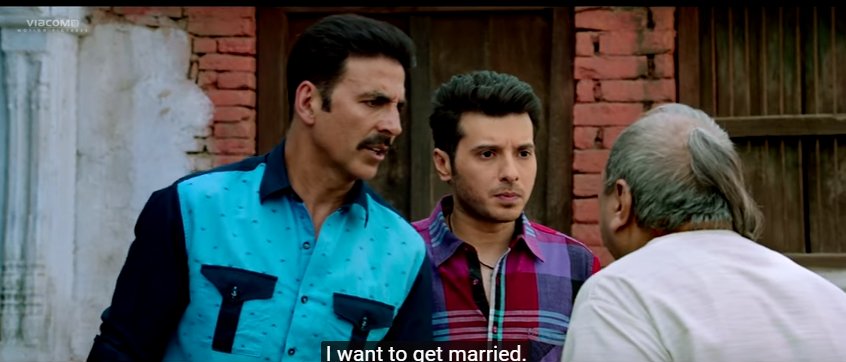

Here, Keshav (Akshay Kumar) is a lovable bachelor from a village in UP. He is in the Raja Babu mould, a no-gooder who desperately wants to get married.

His father is a devout Brahmin, who steadfastly holds on to sanskar and rituals. And because the man also believes in astrology, Keshav can only get married to a girl who has, wait-for-it, a double thumb. Just in case we don’t know what a double-thumb looks like, the hero’s brother breaks into to an Ek-pal-ka-jeena jig every time the topic of Akshay Kumar’s marriage crops up. Am sure Hrithik will be good sports about it. Because, you know, bros can make jokes on bros.

Akshay’s steadfast father (Sudhir Pandey), has already got him married to a buffalo called Mallika (we have to see how Ms Sherawat reacts to this) because he is also manglik. Cue for Bhabhi and milk jokes. Meanwhile, life goes on in the village. Poop and piss gurgle down the drain as Akshay Kumar rides a Honda bike wearing half-sleeved vests and terrycot pants with sneakers. To be fair, he looks adequately small-townish.

Eventually, he bumps into Jaya (Bhumi), a girl roughly half his age with double the number of degrees he has. She is a state-level topper whose face adorns billboards of coaching classes.

Guess what. Unbridled stalking ensues. Stalking which involves a middle-aged man surreptitiously taking pictures of a girl considerably younger than him, without her knowledge.

When the girl, rightly, shames him for the act, she is shown her place by the man. He says that he may be older than her, but he is more “fit” than any youth of the village. Errm. You know what he means by that right?

Also, he loves her.

Not surprisingly, the heartfelt speech by her stalker inspires Jaya to be less of a shrew. Now, she starts pining for him, as she rightly should. Before you know it, she is wearing a prosthetic thumb and demurely kicking the shagun ka kalash at Keshav’s house.

Once the suhaag raat is over, there is an urgent knock on the window at the crack of dawn. The new bride opens it to be greeted by a crowd of ghoonghat-framed faces. The lota party wants her to join them for the early morning dump-taking ritual in the woods.

Ta da da.

Vilain ki entry.

Jaya, who is used to the luxuries of life, like toilets with running water, can’t make peace with this part of her new life. She sulks and makes her displeasure apparent by clanging utensils loudly and making Akshay Kumar peel lauki.

Her husband tries his best to make her life easier but his father glowers with Brahminical indignation. A household with tulsi in aangaan cannot house a toilet. Yada, yada.

Eventually, she has enough of jhaadi mein dump-taking and heads back to her parent’s house. “I am not coming back till you find me a permanent solution,” she tells her hapless husband.

The hero, with generous help from the government, sets out to bring a potty revolution in his village to get back his love. At the end, love and sanitation triumphs. As does Modiji.

In his struggle to get toilets to his village, the protagonist confronts smug government officials. What about the scams worth thousands of crores, he asks them. That’s when he is told by the smug government official that it’s not the government’s fault that backward villagers are not making use of Modiji’s Swachch Bharat Abhiyan. He makes an audio-visual presentation showing how hard the government is trying to get villagers to get toilets in their households, but these backward villagers enjoy defecating in the open.

Thus, the government should be absolved of all responsibilities. Keshav nods his head in grave approval.

This gross over-simplification of the complex issue makes Toilet Ek Prem Katha a problematic film to say the least.

And that’s not all. In the end credits, it’s stated that the film is based on the life of a young woman called Anita Narre from Madhya Pradesh who left her husband’s home and returned only after he built her a toilet. As this review by Anna MM Vetticad points out, Anita’s story happened two years before the Narendra Modi government came to power, yet this film pointedly sets its heroine’s actions in Modi’s time.

Even the film’s most ardent champions would likely concede that Toilet Ek Prem Katha is a spectacularly weird film to end up at the center of a free speech brouhaha.

(All images source from Viacom)